Gendercide in India

What is Making a Difference?

Introduction

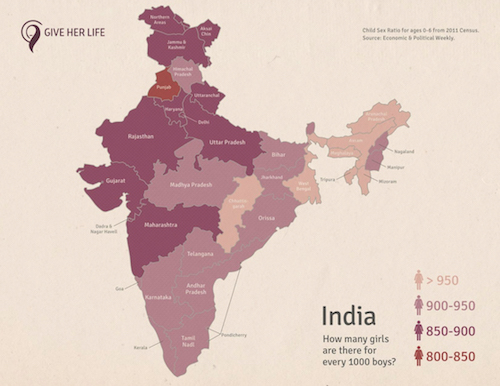

Gendercide, or the elimination of daughters from society, has been occurring in India for centuries. Because of modern technology, people are now able to use sex selective abortion as a method to ensure sons, and not daughters, are born. The child sex ratio (CSR), or the amount of girls there are to the amount of boys in a society, is the best way to track how many daughters are missing. A normal CSR is about 100 girls to every 107 boys. In parts of India, it is upwards to 121 boys for every 100 girls. Hudson et al.[1] asserts, “…the death toll among Indian women as a result of female infanticide and sex-selective abortion from 1980 to the present is almost forty times the death toll from all of India’s wars since and including its bloody struggle for independence.” It is estimated that there are 43.3 million missing girls in India in 2010.[2] See Figure I for a map of India and the child sex ratio at birth in each state.

Figure 1 Child Sex Ratio for Ages 0-6 from India 2011 Census.[3]

Results of the Study

The very abnormal CSR is how we know there is a problem in India. But has anything been done and by whom? The main players in the fight against gendercide are the government of India and civil society groups (nonprofits/NGOs). It is difficult to measure if their efforts have made a difference, but the best way is to look at the CSR before and after an initiative has taken place. Then we see if the CSR got better during their efforts, showing if there was less or more gendercide. I did a study to look at this. The goal of the study was to see if the initiatives were making a difference and I did that by collecting many initiatives and looking at the CSR before and after each initiative.

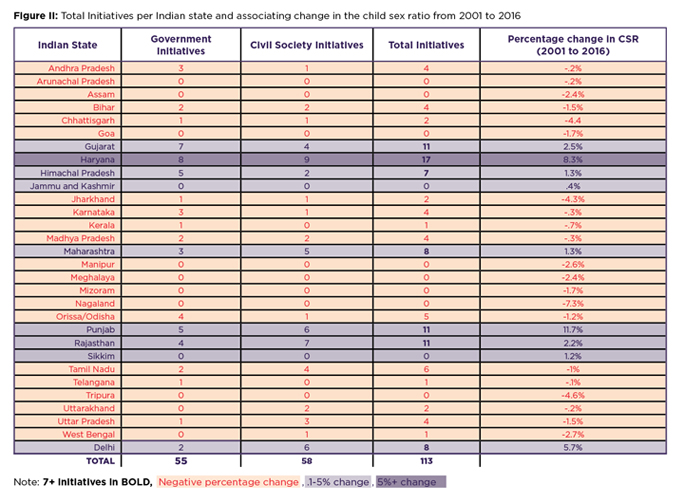

This study collected 112 separate interventions, or efforts, that have occurred in India. The CSR is measured before and after each initiative, indicating if things got better or worse over the duration of the efforts made. The results show that 51% of the initiatives did have a better child sex ratio after initiatives occurred. The most important finding was that states in India that had a lot of initiatives occurring had a better change in the CSR than states that only had a few initiatives. See Figure II for data results.

Best Practices

From these findings, there were several strategies in the initiatives that look like they might be lessening the occurrence of gendercide. These “best practices” are ways that government and civil society groups can make a difference. These best practices — strict, serious enforcement by the government, multi-pronged approach, women’s leadership in policy formation and implementation, in-context methods, and partnership with authority entities — are present in the vast majority of the interventions that had a better CSR after implementation.

Government Best Practices

1. Strict, serious enforcement by the government

The first strategy is serious government efforts to combat sex-selective abortion. For example, in 2005, a “Watchdog” group was established consisting of former police chiefs, the health ministry, and the retired director general of police. Their efforts, which included undercover inspections and legal action against abortion clinics, occurred in five different states. In all five states, the CSR was better after intervention.

2. Multi-pronged approach by the government

The second strategy for the government is a multi-pronged approach that combines a variety of methods, groups and organizations into one initiative. This study shows that these combined effort cases, which include the government and local non-government organizations (NGOs) are essential to making a difference. In Haryana, a multi-pronged approach headed by state government has been underway and includes financial assistance to girls and their families, rewards for districts with improved sex ratio, plays, rallies, pledges by citizens and other publicity. In 2005 the CSR was 823 girls to 1000 boys and increased to 903 girls in 2016,[4] showing that the CSR was much better after intervention.

3. Women’s involvement in the leadership, implementation and policy-making of government schemes

The third strategy is women’s involvement in the leadership, implementation and policy-making of government schemes. For example, in Bibipur, Haryana, an all-women panchayat (village-level administrative group) was put into power. They immediately banned sex selective abortions and passed a resolution that those found participating in female sex selective abortion would be charged with murder.[5] Violators of the ban are also socially boycotted. The women then used government monies by investing in intensive campaigns aimed at tackling issues like dowry and gender bias. They have banned DJs and other celebrations at marriages to minimize dowry expenses. Many women were given assistance in pursuing education, empowering them to become more independent.[6]

Civil Society Best Practices

1. Context appropriate methods

The first strategy for grassroots, civil society efforts is context appropriate methods. These specific context appropriate methods are how activists have used language and slogans appropriately, set culturally sensitive goals and addressed correct audiences. These strategies were particularly important in education and media campaigns. In Morena, Madhya Pradesh, the NGO Prayatn has taken great care in creating context appropriate interventions by creating a rapport with the city and its citizens, giving training and education to men and women about women’s legal and reproductive rights, and organizing a cadre of local women activists.[7] During Prayatan’s initiatives, the city of Morena saw a 9% positive change in the CSR.

2. Partnering with local authority entities

The second strategy for civil society groups is partnering with local authority entities. The authority entities, usually local government and religious bodies, hold authoritative sway in many communities, thereby adding soft power to civil society efforts. In one example, several groups (including UNICEF, UNFPA and religious leaders) teamed up to walk 2,000 kilometers across five Indian states.[8] The pilgrimage concluded in the holy city of Amritsar on a religious Sikh holiday. Sikh religious leaders condemned sex selective abortion and threatened that any patrons found to be participating in the practice would be excommunicated. Of the five states visited, four saw a significant positive change in the CSR.

3. Sponsorship of local Indian NGOs by international NGOs

The third best practice for civil society groups is sponsorship of local Indian NGOs by international NGOs. For example, in Haryana, ActionAid India has sponsored many local groups (including women’s rights groups, academics, and activists) to conduct carnivals, advocacy, education, celebrations of baby girls’ births, etc. During their campaign, Haryana saw a 6.4% positive association with the CSR, showing that the initiative may have made a difference.

Conclusion

In 2008, the Indian Prime Minister declared, “No nation, no society, no community can hold its head high and claim to be part of the civilized world if it condones the practice of discrimination against one half of humanity represented by women”.[9] The Prime Minister then outlined specific government campaigns to end sex selective abortion in several states throughout India. This study shows that some of this work by government and civil society groups may be making a difference in a few states in India. There is, however, a generous amount of work, policy implementation, and grassroots effort that need to be made before a balanced child sex ratio is achieved.

[1] Hudson, V. M., Ballif-Spanvill, B., Caprioli, M., & Emmett, C. F. (2014). Sex & world peace. New York: Columbia University Press.

[2] Bongaarts, J., & Guilmoto, C. Z. (2015). How many more missing women? Excess female mortality and prenatal sex selection, 1970-2050. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 241–269. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00046.x.

[3] Census of India: Census data online. (2011). Retrieved February 10, 2017, from Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdataonline.html.

[4] Thakur, M. (2016, January 22). Beti Bachao delivers gains in Haryana, but gaps remain. Retrieved February 21, 2017, from http://www.livemint.com/Politics/p6CEyeHkxxZckdx7RTiWON/Beti-Bachao-delivers-gains-in-Haryana-but-gaps-remain.html

.[5] Sandhu, K. (2015, June 12). Haryana village initiates contest for ‘best selfie with daughters’: Beti Bachao, Selfie Banao. Retrieved February 10, 2017, from indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/win-win-contest-is-rage-in-haryana-village-beti-bachao-selfie-banao/.

[6] Siwach, S. (2016, July 14). Activists to adopt 2 Haryana villages having worst sex ratio - Times of India. Retrieved February 21, 2017, from timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Activists-to-adopt-2-Haryana-villages-having-worst-sex-ratio/articleshow/46362986.cms.

[7] Gender Equality & Social Justice. (2014). Retrieved July 21, 2016, from Prayatn, http://www.prayatn.org/gesj.html

.[8] Adorna, C. (2005). UNICEF endorses multi-faith campaign against female foeticide. Retrieved July 19, 2016, from UNICEF India, unicef.in/PressReleases/265/UNICEF-endorses-multifaith-campaign-against-female-foeticide.

[9] Srinivasan, S., & Bedi, A. S. (2011). Ensuring Daughter Survival in Tamil Nadu, India. Oxford Development Studies, 39(3), 253-283. doi:10.1080/13600818.2011.594500.

comments