Translating Familial Biblical Terms

An Overview of the Issue

This article is an abridgement of “A New Look at Translating Familial Language,” forthcoming in The International Journal of Frontier Missiology 28:3 (2011).

A well-educated non-Christian woman was reading the Gospel of Luke for the first time. She came to Luke 2:48, where Mary says to Jesus, “Son,…Your father and I have been anxiously searching for you” (ESV). The woman said, “I can’t accept this! We know that Jesus was born from a virgin and did not have a human father!” She protested strongly that Joseph could not have been Jesus’ biological father, and she cited this statement in Luke as “proof that the Bible has been corrupted and is unreliable,” meaning the translation was corrupt. What could have been the cause of her misunderstanding?

The Difference between Biological and Social Familial Terms

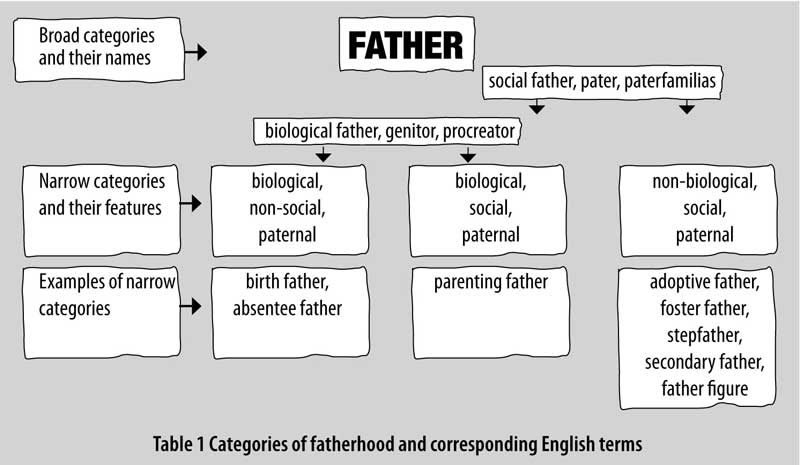

The problem for this woman was that the word used for father in the Bible translation that she was reading is biological in meaning. It is not normally used for non-biological fathers, such as stepfathers and adoptive fathers. Thus it implied that Joseph had sired Jesus by having sex with Mary. The word was equivalent in meaning to the English words biological father, genitor, and procreator, rather than to social father, pater, or paterfamilias. The biological father is the one who begets the children. The social father is the one who raises the children as their father, looks after them, and has authority over them.

In a typical family, the same man is both the social and biological father, i.e., he is a parenting father, meaning he is the provider of both paternal DNA and paternal nurturing to the same child. In some cases, however, the social father of a child is not the biological father. An adopted child, for example, has an adoptive father and a birth father. These categories are shown in table 1.

Table 1 Categories of fatherhood and corresponding English terms

It is crucial to note that social father and biological father are overlapping categories, and a parenting father is in both categories. So a man can be described as a child’s social father without implying that he is the child’s biological father as well, even if most social fathers are also the biological fathers of the children they raise. In Luke 2:48–49, both Joseph and God are called in Greek Jesus’ patêr “social father.” Since neither one passed DNA to Jesus, the paternal relationship was not only social but also non-biological.

As shown in table 1, the English word father is broad in meaning and not necessarily biological, since one can be a father to someone without having sired him or her. In some languages, however, the word commonly used for a paternal family member is limited in meaning to biological father, so it is not used of a stepfather or adoptive father. In the translation read by the woman above, the word used to translate patêr “social father” actually meant biological father; this implied that Joseph had sired Jesus and hence that Mary was not a virgin when she conceived him. It was not an accurate translation.

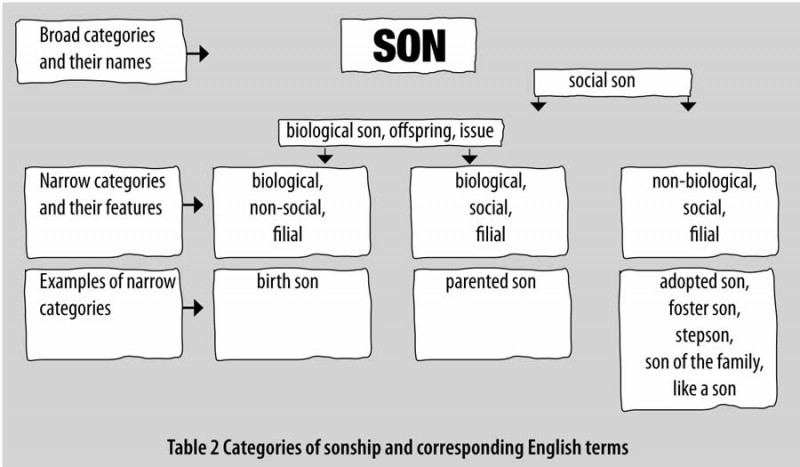

A similar distinction exists between social son, which signifies a filial social relationship to a father, and biological son, which signifies a filial biological relationship to the source of one’s paternal genes. Again, in a typical situation the same person has both relationships; a parented son receives his DNA and paternal nurturing from the same man. In some situations, however, this is not the case; Jesus received paternal nurture from Joseph but did not receive DNA from him. These categories are shown in table 2.

Table 2 Categories of sonship and corresponding English terms

The English word son covers all three categories, but in some languages the word commonly used for a male child of the family is limited in meaning to biological offspring. Such a word does not accurately describe Jesus’ relationship to Joseph.

Biblical Greek and Hebrew have one set of terms signifying social familial relationships, similar to English father and son, but with broader application, and a second set for biological familial relations, like English procreator and offspring.2 In a nurturing biological family both sets of terms apply to the same people. A stepson, however, is not called a biological son, and a disowned biological son is no longer a social son.

It is important to realize that to express divine familial relationships, the Bible uses the Greek and Hebrew social familial terms, not the biological ones. It presents the essence of God’s fatherhood of us in his paternal care for us as his loved ones rather than in siring us as his biological offspring.

While in Hebrew and Greek the social familial terms are the ones commonly used to refer to members of one’s family, in some languages the biological terms are most commonly used. Other languages, like Arabic and various Turkic languages, lack a set of social familial terms, and neither adoption nor step relations are recognized, so to convey a non-procreated familial relationship one must use a phrase, such as like a father to me, or use a term for paterfamilias (head of family). When translating the Bible into such languages, it would be inaccurate to translate the Hebrew or Greek word for a social father or son using a word for a biological father or son in the target language unless the relationship is truly biological. This is especially the case with regard to the Father-Son relation, which was generated non-biologically, without procreation. Translating Father and Son with biological terms has caused readers to think the text claims that Jesus is the offspring of God procreating with Mary, and this has caused Muslim readers to reject such translations as corrupt and even blasphemous.

Problems with Mixing up Biological and Social Familial Terms

It is the task of Bible translators to communicate “the meaning of the original text…as exactly as possible…including the informational content, feelings, and attitudes of the original text” by re-expressing it “in forms that are consistent with normal usage in the receptor language.”3 It might seem astounding, therefore, that Bible translations would ever use expressions that misrepresent the divine relations by implying they arose from sexual procreation. However, this has happened in the history of Bible translation for two reasons. One is that translators have historically preferred word-for-word translations of key biblical terms. Some translators are under pressure to do so even if it misrepresents the meaning, as it can when the target language requires the use of a phrase to express a non-biological familial relation. Another reason is that some translators simply used the most common words in the target language for all familial relationships, even if those words were biological in meaning and a different, specialized term was required to express the social or non-biological relationships in the family of God.

The reality is that there are usually semantic mismatches between the words in any two languages, especially if they are from different language families and different cultures, and translators often have to use phrases in the target language to express the intended meaning of a single term in the Greek or Hebrew text. Not understanding this, some well-intentioned Christians have insisted that the Bible translators in other countries produce word-for-word translations of familial terms because they mistakenly assume that every language describes familial relations in the broad sense expressed by the common English, Hebrew, and Greek familial terms. But that is not the case, and the common, single-word terms used for family members in some languages are strictly biological and are inappropriate for describing the family of God. The problem is that these translations end up attributing a biological meaning to the fatherhood of God, implying he reproduced the Son, the angels, or even the spirits of people through sexual activity. This meaning was not communicated by the original-language expressions, and it conflicts with the intended meaning of the text.

This mistake results in readers understanding the Lord’s Prayer to say “Our Begetter, who is in heaven,” and understanding Jesus to be “God’s (procreated) offspring.” The “longing of creation” (Rom 8:19) is understood to be “for the revealing of God’s biological children.” Such wordings are inaccurate because they add a procreative meaning that was absent from the original, and they sideline the important interpersonal relationships that were expressed in the original text. Readers from polytheistic religions readily accept that gods procreate with goddesses and with women, and they assume the phrase Offspring of God signifies a procreated origin. Readers in many Muslim language groups understand Offspring of God in a similar way, namely that it means God had sexual relations with a woman; unlike polytheists, however, they reject this possibility and consider the phrase to be a blasphemous corruption of the Bible that insults God by attributing carnality to him. They fear that even saying such a phrase will incur the wrath of God. These misunderstandings disappear, however, when translators express the divine familial relationships in ways that do not imply sexual activity on the part of God. Muslim readers and listeners can then focus on the message without being preoccupied with the fear of attributing carnality to God, and when they do, they recognize that the deity and mission of Christ is evident throughout the Gospels. This highlights the fact that translators are not trying to remove original meanings from the translation that might offend the audience. On the contrary, their concern is to avoid incorrect meanings that fail to communicate the informational content, feelings, and attitudes of the original inspired text.

Some Possible Translations for Father and Son of God

If translators wish to avoid those mistakes and express the divine familial relations in non-biological terms, then what expressions can they use?

- Obviously, in languages that have single words for social fathers and sons, if phrases like our Father and sons of God are understood as signifying God in his caring, paternal relationship to us as his loved ones, without implying a claim that God produced our bodies or spirits by having sex with females (as even Mormons claim), then these expressions are to be preferred.

- In some languages where the commonly used kinship terms are biological, there are also social familial terms similar in meaning to paterfamilias and loved ones (meaning one’s beloved family), and Christians use these to describe God’s paternal relationship to us and our filial relationship to him.

- Where such terms are not available, it is sometimes possible to say something like our God in heaven, who is like a procreator to us, and we are like offspring to God. On the other hand, a phrase like God’s loved ones may be better at conveying the loving nature of the relationship.

- To describe the Father-Son relationship, some languages add a word that helps block the biological meaning of the words, using phrases equivalent to Offspring sent from God or Spiritual Offspring of God.

- Some languages have terms for a favorite son, only son, firstborn son, or ruling-heir (who is usually the firstborn), and people use these for the Father-Son relationship, as in God’s Loved One and God’s Only One. The Greek New Testament uses terms for Jesus equivalent to all four of these, but it also has a term for social son, huios, that is used more often. Unfortunately many languages lack a term equivalent in meaning to huios.

Translators ask people from the intended audience, both believers and others, to read or listen to passages of Scripture in which these alternative wordings have been used; then they ask them questions to find out what they understood these phrases to mean in context. Based on this feedback from the community and feedback from other stakeholders, the translation team and the local editorial committee, with the help of an outside translation consultant, decide which translation is best. There may be several cycles to this testing phase until the best solution is found.

Using the Paratext

The authoritative text of Scripture is the one God communicated to us in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. The task of translators is to enable readers to understand the message that God communicated via this original text. Because of differences in language and context, to communicate God’s message in another language requires both text and paratext. The paratext can effectively define the biblical meaning of an expression used in the translated text as long as that expression does not already mean something contrary to biblical meaning.

The paratext consists of any introductory articles, footnotes, glossary entries, and parenthetical notes in the text that the translators wrote as an integral part of the translation to explain terms, unfamiliar concepts, and essential background information. So even if translators find a way to express divine fatherhood and sonship in the text, it is also important to fill out the meaning of the expression in the paratext. In a non-print Scripture product, the paratext consists primarily of introductions to sections of text. So what should be included in the paratextual explanation of Son of God?

Components of the Meaning of Son of God

Church history and contemporary scholarship emphasize two components of meaning of the term Son of God:

- Ontological (as the eternal Son he is consubstantial with the Father and eternally generated from him in a non-procreative way; Heb 1:3); and

- Mediatorial (as Son of God he is sent by the Father to mediate God’s rule, grace, and salvation to his people, to impart sonship to them, and to be their Savior and Advocate).

Bible scholars suggest that the mediatorial meaning is the most prominent in many contexts of Scripture, but they also recognize that the Bible uses the phrase with six additional components of meaning: familial/relational, incarnational, revelational, instrumental, ethical, and representational. All these can be explained to readers in the paratext, usually in a mini-article, in the glossary, and in footnotes. While the mini-article goes into depth of meaning, the explanatory notes remind the audience that the phrase “Son of God” does not mean God’s procreated offspring but means that he is the eternal Word of God (ontological and revelational), who entered the womb of Mary (incarnational) and was born as the Messiah (mediatorial), and relates to God as Son to his Father (familial).

Preference for the Familial Component of Meaning

Although the concept signified by Son of God is rich in meaning, there are advantages to expressing the familial component in the text and explaining the other components in the paratext. This provides for consistency among translations and consistency with church tradition. More importantly, it is primarily the familial component of divine sonship that Christ imparts to believers, and he is the “firstborn among many brothers,” all under the paternal care of God as loved ones in his eternal family. This is not easily communicated if the familial component of Son of God is not expressed directly in the translated text.

Although Bible scholars agree on the prominence of the Mediatorial meaning of the term Son of God in most New Testament contexts, yet because of the advantages of expressing the familial component in the text, it is clearly best to do that and to explain the mediatorial and other components in the paratext. In particular, we believe mediatorial terms like Christ or Messiah should be used only to translate Greek Christos and should not be used to translate words like Son.

Clarifying Some Misperceptions

There have been a number of misperceptions about the translation of divine familial expressions, especially in languages spoken by Muslims, and these have been aggravated by the current level of tensions in the world. The explanation above clearly states that this is a linguistic issue, in which translators seek to communicate the social familial meanings of the Greek and Hebrew expressions while avoiding the wrong meaning that God reproduces children through procreation. This is the meaning of accuracy in translation. But it might be helpful to address the misperceptions as well:

Contrary to what some people imagine, the use in translation of non-biological expressions for Father and Son

- is not imposed by outsiders, but is decided by believers in the language community;

- is not limited to languages spoken by Muslims but is a challenge for any language in which the normal kinship terms are biological in meaning and imply procreation;

- is not intended to lead audiences into any particular form of church, whether Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox, or “insider”;

- does not itself constitute an “insider” translation or even a “Muslim-idiom” translation;

- is not contrary to normal translation principles but seeks to follow them, by using phrases to translate the meaning of Greek and Hebrew terms that lack a semantic counterpart in the target language, and by explaining the meaning of the terms in the paratext;

- is not limited to “dynamic” translations but is used in more “literal” ones as well;

- is not contrary to how conservative Biblical scholars interpret the Greek and Hebrew expressions but rather seeks to follow their scholarship;

- is not intended to change or obscure the theological content of Scripture or make it more palatable to the audience, but seeks rather to convey it as accurately as possible;

- does not hinder the audience’s perception of Jesus’ deity but rather facilitates it;

- does not stem from liberal or unorthodox theology on the part of translators or from a liberal view of Scripture, but from interaction with the interpretive and theological tradition of historic Christianity and the results of contemporary conservative scholarship, with the goal of communicating the verbally inspired message of the Bible as fully and accurately as possible.

Various Bible agencies are seeking to explain translation principles and dispel these misperceptions. Wycliffe Bible Translators (USA), for example, includes the following point in its statement of basic translation standards:

In particular regard to the translation of the familial titles of God we affirm fidelity in Scripture translation using terms that accurately express the familial relationship by which God has chosen to describe Himself as Father in relationship to the Son in the original languages.4

It is not accurate to use expressions which mean Jesus’ sonship consists of being the offspring of God’s procreation with a woman.

Conclusion

In order to accurately convey divine fatherhood and sonship, translators need to use expressions that are as equivalent in meaning as possible to the Greek and Hebrew terms for social son (huios and ben) and social father (patêr and âb) and to avoid biological expressions of the form God’s Offspring or the Procreator of our Lord Jesus Christ, because these are understood to signify biological relations generated through a sexual act of procreation. In this way translators can enable new audiences to understand the biblical sense in which God is our father and Christ is his son, as well as understand the relationship of Joseph to the boy Jesus.

Ultimately it is comprehension testing that plays the crucial role in the process of translation, because there is no other way to ascertain what a particular wording in the text and paratext actually communicates to the audience or to discover which wordings communicate most clearly and accurately. That is why translators and churches “test the translation as extensively as possible in the receptor community to ensure that it communicates accurately, clearly and naturally.”5 Across the world, this approach to first-time translations has been found repeatedly to offer the best success at enabling new audiences to comprehend the biblical message and to respond in faith, as God enables.

comments