Bible Translation 3.0

Empowering the Global Church to Bring Abundant Access to the Scriptures to Every People

Bible Translation in Transition

A major transition is occurring in Bible translation. This transition has been triggered by a foundational shift of historic proportions: the ownership of and authority over all aspects of Bible translation is returning to the global Church.

It is assumed that where the Church exists in a people group, it is considered to be the spiritual authority for that people group. Where the Church does not yet exist in a people group, the Church in people groups that are geographically or socially close to and missionally focused on the unreached people group (the “proximate Church”) has the clearest perspective of the need and opportunity for translation of biblical content as part of evangelistic outreach and church planting. As such, the proximate church in these contexts is considered to have the primary responsibility for the unreached people group, until the church is present in the people group. At that point, the ownership of and authority for the process of Bible translation is expected to transfer to them.

This transition of Bible translation back to the church would be significant at any point in history. What makes this transition even greater in impact and speed is that it is happening in the Digital Era where mobile phones are nearly ubiquitous, bridging the so-called “digital divide” all over the world. For the first time in history, the global Church—soon to span every people group and language—is equipping themselves with digital technology that is not only useful in the distribution of translated Scriptures, but can play a key role in the Bible translation process itself.

A New Paradigm

In 1876, a revolutionary breakthrough representing decades of research and development by many different inventors finally occurred: the first telephone call was made. The landline telephone was an invention that forever changed the way people communicate. Over time, it became so common in many parts of the world as to make life without it difficult to imagine.

In 1973, another revolutionary breakthrough occurred: the first cell phone call was made. The technology took some time to mature, and then all of a sudden it reached a tipping point and disrupted everything.[1] By the end of 2013, just four decades after its invention, nearly seven billion mobile phone subscriptions were active worldwide—a global penetration rate of 96%. By comparison, it took the landline telephone nearly 14 decades to connect just over one billion people, a global penetration rate of approximately 16%.[2]

The massive increase in capacity, usefulness, and reach that occurred in the global shift from “landline telephone” to “Internet capable, multimedia mobile phone” in no way diminishes the importance and significance of the landline telephone. The telephone launched a new era of communication and freedom that had never before been possible. It was an extremely important paradigm shift. It just wasn’t the last one.

This article describes a paradigm shift occurring in the realm of Bible translation.[3] The emerging paradigm is clearly indicating that the changes ahead may bring exponential increases in capacity, usefulness, and reach to Bible translation. Not only does this paradigm greatly increase efficiency and cost-effectiveness, it can be extended to reach literally every single people group with the Word of God in their own language, with no exceptions. In the same way that the mobile phone surged past the landline telephone to connect the entire world to each other, this new paradigm in Bible translation appears poised to connect speakers of every language in the world to the Word of God.

This article describes a paradigm shift occurring in the realm of Bible translation.[3] The emerging paradigm is clearly indicating that the changes ahead may bring exponential increases in capacity, usefulness, and reach to Bible translation. Not only does this paradigm greatly increase efficiency and cost-effectiveness, it can be extended to reach literally every single people group with the Word of God in their own language, with no exceptions. In the same way that the mobile phone surged past the landline telephone to connect the entire world to each other, this new paradigm in Bible translation appears poised to connect speakers of every language in the world to the Word of God.

In the process of describing a new paradigm, it is necessary to explain what is changing and (where possible) why the change is occurring. The objective of this article is to describe these changes with clarity and in a balanced manner. Before describing the transitions that are occurring, we will briefly consider the history of Bible translation.

A Brief History of Bible Translation

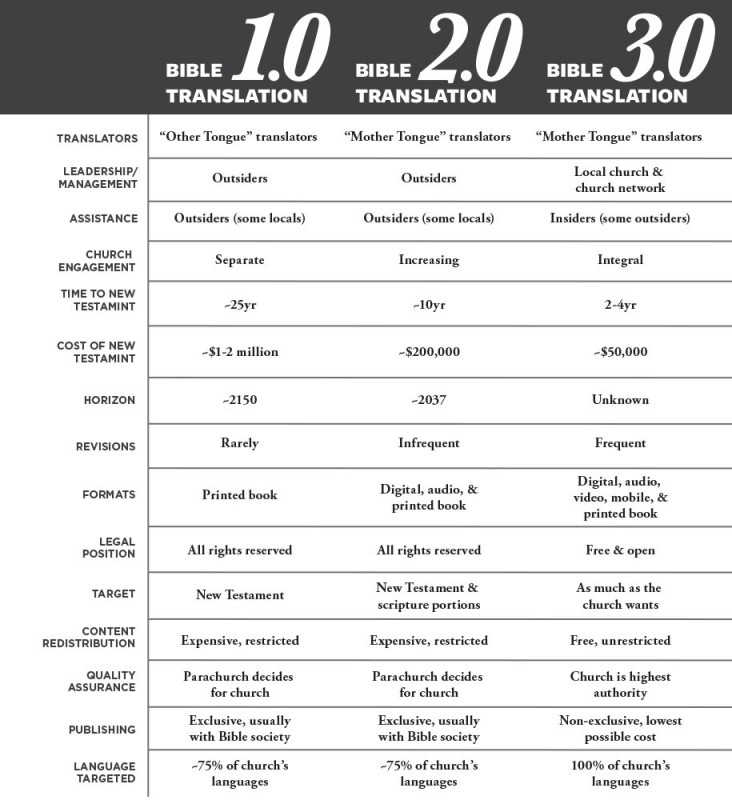

The patterns of Bible translation in the past 2,000 years can be separated into three fairly distinct eras. The objective of translators in each era was generally the same: translate the Bible into other languages with the highest possible degree of faithfulness. Certain factors changed through time, such as the availability and quality of original language source texts. The key factors that we are considering are those of the ownership of the Bible translation process and the efficiency of the work.

The Historical Era (pre–1800s)

This era covers the time from the translation of the Septuagint through the translations during the Reformation and the colonial expansions of the 17th and 18th centuries. In general, the vast majority of the translations completed during this era were done by members of the Church into their own “mother tongue.” For example, Ulfilas was ordained a bishop of the Church and translated the Gospels and some Epistles into his own Gothic language (360 A.D.). Jerome was born and raised in a Latin-speaking Roman province and translated the Bible into Latin (circa 405 A.D.). Wycliffe and Tyndale translated into their native English. Luther translated into his native German.

By the year 1800, there were 40 languages that had a translation of the Bible and another 27 that had some Scripture. [4]

Bible Translation 1.0 (1800s-Present)

In the early 1800s, two significant events occurred in the realm of Bible translation: the first Bible Societies were formed and the so-called “Modern Missionary Movement” began. The efforts of missionaries like Robert Morrison, William Carey, Adoniram Judson, Henry Martyn and many others saw Bible translation expand far beyond Europe into many of the world’s major languages. In the 20th century, other Bible translation organizations were established that helped accelerate the work.

In this era, the work of Bible translation was often tied to the work of evangelization of unreached people groups. In some places, Bible translation preceded church planting. In general, the Bible translation process during this phase was owned and operated by those outside the target culture and language. Missionary translators studied linguistics, defined orthographies, and wrote grammars of previously undocumented languages, with the goal of making an effective translation of the Bible into them. The net result of the work in this era was a significant rise in availability of the Word of God in other languages.

By 1982, the entire Bible had been published in 279 languages, the New Testament in 551 more, and at least one book of the Bible had been translated into 933.[5]

Bible Translation 2.0 (~1980-Present)

In the early 1980s, a shift in Bible translation strategy began to be implemented by some organizations. Whereas the actual work of translation in the preceding era was generally done by expatriate translators, some translation teams began using native speakers to do large parts of the translation work. Frequently, these translation projects were still managed and funded by outsiders, but signs that a broader shift was taking place began to be visible.

By 2011, the entire Bible had been translated into 471 languages, the New Testament into 1223, and Scripture portions had been translated into another 1,002 languages.

Bible Translation 3.0 (Digital Era)

The transition that began in the preceding era is completing its trajectory: the responsibility for and ownership of all aspects of the process of Bible translation in the Digital Era are returning to the global Church. This foundational transition affects every aspect of Bible translation, and we will consider each element in detail below.

The Status of Bible Translation Today

As the global Church continues to rise to the challenge of learning to translate the Bible into their own languages, it is important to understand the status of Bible translation in relation to the world’s languages today. Arriving at accurate statistics regarding the status of Bible translation worldwide is a complicated undertaking. Arguably the best statistics available to the global Church are compiled by the Wycliffe Global Alliance and are available online at http://www.wycliffe.net/statistics These. are the statistics as of 2013 assembled as a chart[6]:

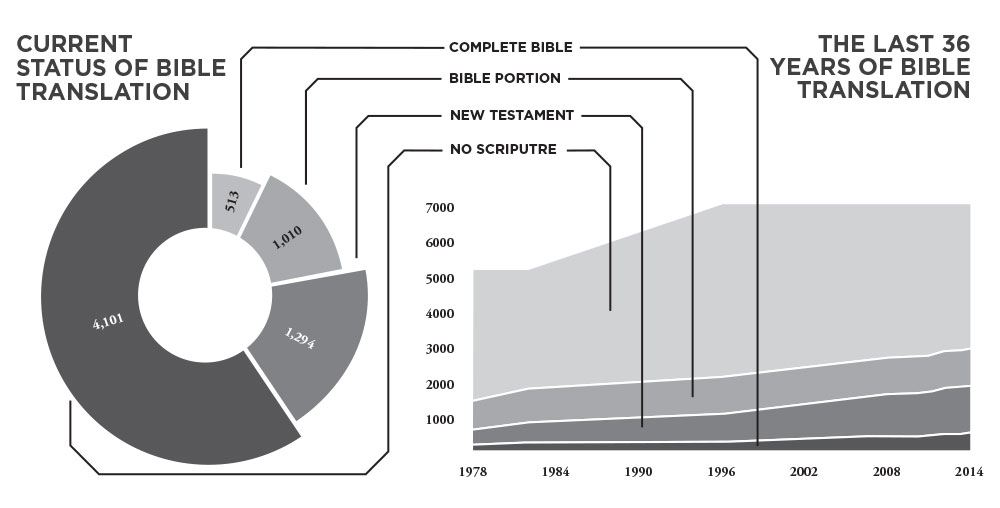

The numbers in this chart are arrived at by adding the known number of translated Bibles (513), the number of New Testament translations (1,294), and the known number of languages with translated Scripture portions (1,010), then subtracting that total from the known number of living languages (6,918) to arrive at the number of living languages without any Scripture (4,101). These numbers do not show languages with work in progress (see below) or imply anything with regard to assumed need or desire for translation. The chart also does not show the number of translations in the list that are listed as “finished” but are not in use because of the need for revision of the translations. Some estimates put the number of languages that have translated Scripture in need of revision as high as 400–500.

The chart above (“status of Bible translation”) is a snapshot of the current status of languages and Bible translation today. A more complete picture is provided by tracking the progress of Bible translation through time. Detailed records are not publicly available from before 1978. This chart (“The Last 36 Years of Bible Translation”) shows the progress of Bible translation as compared to the known number of living languages through time for the past 36 years[7]:

Bible Translation in the Past 200 Years

This table is based in part on research done by Wycliffe Associates and provides a general overview of key aspects of Bible translation:

The Significance of Each Language

In light of the reality that over 4,000 languages still do not have translated Scripture, it is important to consider the value of each language in light of Scripture and the sociolinguistic context of the world today. Scripture seems to suggest that the value God places on each people group and each language is equal, regardless of the number of speakers. In the Great Commission of Matthew 28:18–20 the Church is given the task of making disciples of “every people group.” In the vision of the global Church before the throne of God are the redeemed from “every nation, tribe, people and language” (Revelation 7:9).

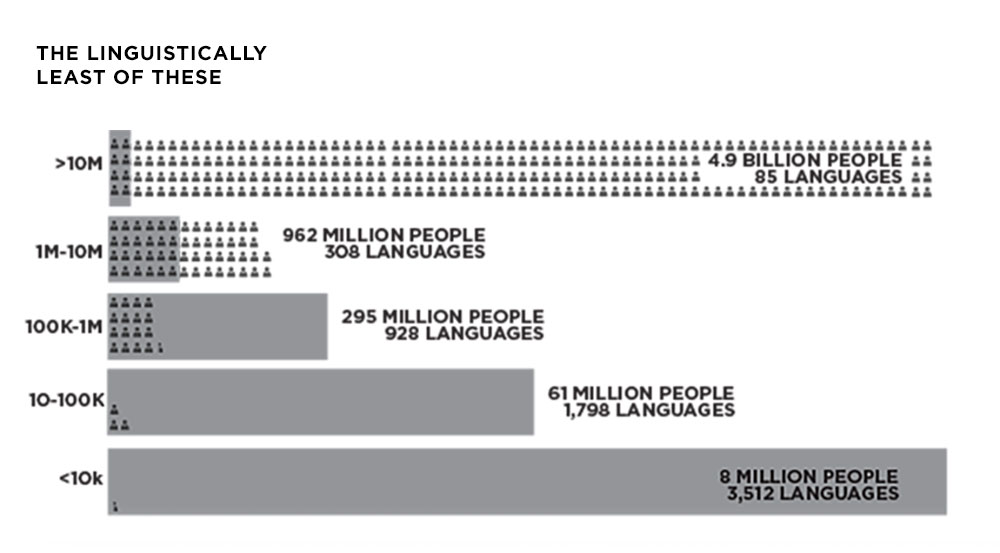

One approach is to prioritize languages based on the “return on investment” of a translation project. If someone is going to pay money to translate a resource into a language, the logical approach is to start with the languages that have the most speakers and work down from there. This makes great business sense, but it falls short in accounting for the missiological reality that if this is the only strategy employed, the last and the least will continue to wait indefinitely to get biblical content. Translated biblical content may never get to the last and the least in this model, because there is a point where the cost eventually exceeds the perceived value to the owner of the process.

This chart (“the linguistically ‘least of these,’” created from the language data available at http://www.ethnologue.com) shows the breakdown of the populations of every language in the world, by number of speakers:

The top row shows the number of languages (85) that have more than 10 million speakers each. The combined populations of these largest languages is 4.9 billion people. By contrast, the bottom row shows the number of languages (3,512) that have fewer than 10,000 speakers each. The combined population of these languages (more than 50% of the living languages in the world) is around eight million.

A Partial Solution

To illustrate the challenge intrinsic to the institutional model for Bible translation, consider the analogy of the landline telephone and the mobile phone. Telecommunications companies that deal in landline telephones have to make difficult decisions about where (and how far) to extend their reach. Running cables and building telephone poles is time-consuming and expensive because landline telephones and the infrastructure that make them work are inherently scarce. In the world of scarcity, not everyone gets reached, simply due to the high costs associated with the infrastructure required to deliver the service.[8]

By contrast, the mobile phone world is driven by an abundance model. It costs the telecommunications company virtually nothing to add another mobile subscriber to a wireless network. Any mobile phone kiosk can sell someone a SIM card, and the only additional hardware required is a mobile handset, which the consumers pay for themselves. Even when huge numbers of subscribers join, the cost of putting up new cell towers to accommodate new users is vastly less than trying to build and maintain telephone poles and lines across an entire country.

So the telecommunications companies that are attempting to solve the communication problem by using landline telephones must choose who gets and who does not get a telephone, based on their organizational capacity and the inherent costs of using landline telephones. This external, top-down, unilateral determination by the power-holder is intrinsic to the scarcity era. It is unavoidable. The landline telephone company might reason that some villages are close enough to other villages so that phones in one village could be used by the people in the other. The objective could become one of providing a telephone for everyone who is considered to have a need for one.

Things become complicated when the inevitable happens: someone from a village not scheduled to receive a telephone line decides they want one. Who wins? Does the telephone company reconsider, given that someone has determined for themselves they actually do need a telephone? More likely, the telephone company may simply not have the capacity to change their decision and the person will just have to go without. The decision in this context does not rest with the person in the village—it rests with the institution.

The institutional model of Bible translation is faced with a similarly unenviable task: deciding which languages of the world will receive Bible translations, when, and how much of the Bible they will receive. While these decisions are not usually made without input from language communities, institutions have limited resources and personnel and, regardless of their desire to the contrary, they are unable to go the distance to the last and the least. So they must prioritize projects and establish a cutoff point beyond which their organizational capacity simply cannot reach.

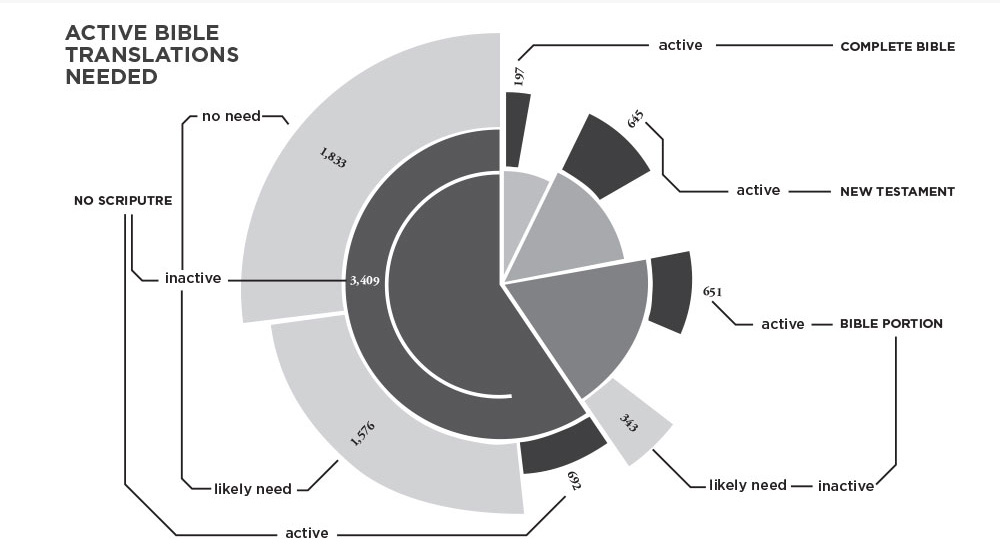

This cutoff point can be visualized by continuing to chart the statistics available to the global Church regarding the collective Bible translation task. In addition to the Bible translations currently available, “there is known active translation and/or linguistic development happening in 2,167 languages… This includes 692 languages for which there is no known Scripture; 197 languages with a Bible; 645 languages with a New Testament; and 651 languages with portions of Scripture, such as a book.”[9] These nine active projects can be displayed in the same chart as follows (“active Bible translations”). Note that the active language projects are labeled on the languages that also have translated Scripture:

From this we can see that the total number or languages with available Scripture or an active translation project covers roughly half of the world’s languages (again, disregarding translated Scriptures needing revision). Of the remaining 3,409 languages having no Scripture or active translation project, “1,919 languages are understood to ‘likely need Bible translation to begin.’ These estimates represent 1,576 languages with no known Scripture... and 343 languages... with some Scripture but no current activities in place.”[10] The criteria by which individual languages are determined to be a “likely need” (or not) are not available to the global Church. The languages determined to be a “likely need” are labeled in the chart to the left (“likely need” for Bible translation).

From this we can see that after we add together all the languages with Scripture, those with active projects (but no Scripture), and those considered to be a likely translation need (but with no Scripture or active project), there are still 1,833 languages that are not accounted for. Presumably, these last 26% of the world’s languages are considered to be too small or too weak (“unviable”) for the institutional model to be able to serve. Because the institution has the authority to make the decision and owns all the tools and resources, their decision is final. Which raises an important question: When the Church disagrees with the Bible translation institution what happens?

The global church is rising up and beginning to determine for themselves that they need the Bible in their own language. It is at this foundational point in the process—the assessment of translation need and priority—that the global church in many languages is in crisis and the transition into Bible translation 3.0 begins. They are in desperate need of God’s Word in their language, but frequently their language is not on the “needs translation” list or the church is no longer willing to wait for others to permit them to start. In some places they have nothing more than a bootlegged copy of Microsoft Word and Bible in a trade language. But the church has assessed their own need for Bible translation, and they are getting started. With or without help.

In Honor of Those Who Have Gone Before

As stated above, the objective of this article is to address topics pertaining to Bible translation with clarity and balance. It would be easy to misconstrue efforts made to objectively assess the limitations of previous Bible translation eras as an attempt to discredit or diminish the work of those who have gone before. Nothing could be further from the truth. The changes in the global context that create new opportunities for the acceleration of Bible translation in every language without limitation do not implicitly suggest that the people, organizations, and strategies of previous eras were deficient in any way. The history of Bible translation is filled with those who have worked with incredible diligence and laid down their lives for the advance of the Gospel in other languages, making the most of the opportunities available to them at the time. They are worthy of honor for their work to that end.

You can learn more about the unfolding Word at http://ufw.io/bt3 You c.an learn more about Wycliffe Associates at wycliffeassociates.org.

[1] Disruptive innovations are is described by Clayton Christensen as technologies that typically underperform established technologies at the outset but, because they are usually cheaper, simpler, smaller, and more convenient to use, they rapidly outpace existing technologies. (Christensen 1997)

[2] “The World in 2014: ICT Facts and Figures” 2014

[3] The concept of a paradigm shift as used in this document is described by Thomas Kuhn: “Normal science is characterized by a paradigm, which legitimates puzzles and problems on which the community works. All is well until the methods legitimated by the paradigm cannot cope with a cluster of anomalies; crisis results and persists until a new achievement redirects research and serves as a new paradigm. That is a paradigm shift...” (Kuhn and Hacking 2012).

[4] Cowan 1983. Some sources suggest higher estimates of languages with available Scripture by 1800.

[5] Ibid

[6] “Scripture Access Statistics 2013” 2013. During the writing of this document, the 2014 statistics were published and are available online. The numbers for the categories in the pie chart for 2014 are as follows: 531 Bible, 1,329 New Testament, 1,023 with Scripture portions, leaving 4,019 languages with no Scripture, assuming a total of 6,902 living languages (see http://www.ethnologue.com/statistics), not including the 204 languages listed as living but having zero speakers. Key data regarding the number of languages included in multiple categories is not included in the 2014 statistics, for reasons not stated.

[7] This chart is arrived at by performing the same calculations as in the preceding chart, with the number of languages in each category in the vertical axis and the years from 1978 to the present running from left to right. The source data is listed in the references for this document. Note that this chart includes data for 1978, 1982, 1996, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013.The values of years for which data is not available are assumed to be the average of the preceding and following years. Note that it is possible the total number of languages worldwide may have been relatively constant in the years preceding the mid-1990s, though the full number of living languages was unknown at the time.

[8] The difference between “scarcity” and “abundance” and the role of digital technology in the rise of the latter is explained by Clay Shirky (2010, p. 42ff).

[9] “Scripture Access Statistics 2013” 2013

[10] Ibid.

comments