Why has the Church Lost “Face”?

Examining Our Blindspot About Honor and Shame

Once again I found myself in the same conversation. The missionary shook his head and said, “That’s fine if you want to talk about ‘face’ as a gospel ‘bridge.’ But, ultimately, you have to talk about ‘law’ if you are going to really share the gospel.” Why do people find it so hard to understand the importance of honor-shame in gospel ministry? “Face” is a Chinese way of talking about honor and shame. Many Westerners have the impression that wanting “face” only has bad connotations, as if such a person is simply “proud.” No one denies that seeking face can express sinful pride. However, concern for “face” is not always sinful. In China, “You don’t want face” (你不要脸), is an insult. Why? Someone who does not want “face” (脸) is immoral and does not care about the opinions of others. They have no “sense of shame” (不知廉耻).

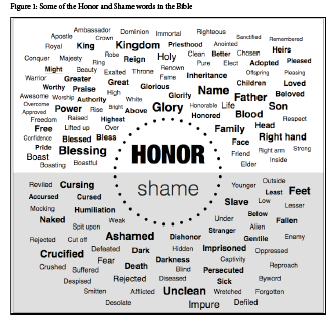

As various scholars have observed, honor/shame (H/S) is “the pivotal cultural value” of the Bible.1 Figure 1 lists a variety of words in Scripture related to H/S. With just a glance, we see that H/S lies beneath the surface of countless biblical passages, relating directly to reputation, respect for authority, group identity, and the gospel itself. And yet the biblical presence and significance of H/S is widely overlooked in the Western theology embraced around the world. This essay seeks to explain why this blindspot exists.

As various scholars have observed, honor/shame (H/S) is “the pivotal cultural value” of the Bible.1 Figure 1 lists a variety of words in Scripture related to H/S. With just a glance, we see that H/S lies beneath the surface of countless biblical passages, relating directly to reputation, respect for authority, group identity, and the gospel itself. And yet the biblical presence and significance of H/S is widely overlooked in the Western theology embraced around the world. This essay seeks to explain why this blindspot exists.

It is not sufficient simply to write off ignorance of H/S in the Bible to “cultural differences” in general. We need to understand the reasons for this oversight. And in removing this blindspot, we will better grasp both the Bible and how it addresses the needs of the people we serve. In what follows, we distinguish culture, theology, and biblical truth to give perspective on why this blindspot exists. We then identify fears that make people reluctant to treat H/S with the same seriousness as the parallel biblical framework of Innocence/Guilt. Finally, we consider the consequences of this H/S blind to the Bible’s teaching on honor-shame? What happens when we maintain a superficial view of H/S?

CONFUSING THEOLOGY WITH BIBLICAL TRUTH

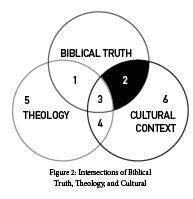

Figure 2 illustrates the interrelationship between biblical truth, theology, and cultural context.2 Note first that biblical truth is larger and higher than any theology. No matter how refined one’s theology may be, it can never be as comprehensive as the totality of biblical truth. Humans have limited knowledge, but God is omniscient; humanity is fallen and fallible, but the Bible is holy and infallible. It follows that every theology is smaller than the totality of biblical truth.

Figure 2 illustrates the interrelationship between biblical truth, theology, and cultural context.2 Note first that biblical truth is larger and higher than any theology. No matter how refined one’s theology may be, it can never be as comprehensive as the totality of biblical truth. Humans have limited knowledge, but God is omniscient; humanity is fallen and fallible, but the Bible is holy and infallible. It follows that every theology is smaller than the totality of biblical truth.

Now let’s examine the six numbered areas.

Area 1 is where biblical truth overlaps with one’s theology but not the cultural context. Here theology reflects biblical truth in opposing cultural practices like abortion or widow burning. Another example is the legal framework for the gospel recognized in Western theology—e.g., “The Four Spiritual Laws.” This has biblical support but fails to resonate with many non-Western cultures.

Area 2 is where biblical truth overlaps with the cultural context without being addressed in one’s theology, such as Heibert’s observation of Western theology’s “excluded middle.”3 This is where blindspots occur, as detailed below.

Area 3 is where one’s theology and the cultural context overlap with biblical truth, as in a high view of the family.

Area 4 is where elements in a theology overlap with a cultural context but not with biblical truth. For example the “prosperity gospel” overlaps with America’s culture of consumerism but not biblical truth.

Area 5 is where elements in a theology overlap with neither biblical truth nor a cultural context, as when a missionary unwittingly carries excessive Western individualism into a community-based, “collectivistic” culture. In a “collectivistic” context, groups largely shape personal identity and the community’s needs are generally prioritized over individual concerns.

Area 6 is where cultural beliefs or values are inconsistent both with biblical truth and a particular theology.4 Since every culture is fallen, any number of beliefs and values fall in this category. An example in American culture is a woman’s alleged “right” to kill her unborn child.

What about the blindspot regarding honor and shame?

Take a closer look at Area 2—where blindspots occur. Why? When crossing cultures, we are naturally less familiar with the local customs and worldview. Since cultures have sinful elements we are naturally suspicious of unfamiliar values and ways of thinking. If we never read the Bible through alternate cultural lenses, we will assume that our own historical theology is comprehensive and flawless, without recognizing that it too has been contextualized within our own Western culture.

Just as all cultures contain sinful elements, so all retain facets of God’s revelation. We should expect every culture to help us see biblical truth that our own culture minimizes or overlooks (as in Area 2). A non-Western lens can help us discover the rich H/S dynamics throughout the Bible. Sadly, this is almost totally ignored by Western theologians; the indexes of systematic theology books have multiple references to guilt but almost none for shame.5 The same is true of familial piety, respect for ancestors, and collective identity. All of these not only were significant facets of the cultures in which the Bible was written; they also are present in many Majority World cultures today— both reached and unreached.

These observations should humble us, causing us to slow down and dig deeper when we read scripture for application in “foreign” contexts. If we don’t, we may inadvertently “assume the gospel” by limiting ourselves to its legal framework without consideration of other 6 biblically faithful and culturally meaningful alternatives. Blindspots occur precisely where we imagine that our own understanding and presentation of the gospel are free of cultural influence. But every gospel presentation is shaped by the cultural values of the presenter and their perception of their intended audience’s cultural values.

These observations should humble us, causing us to slow down and dig deeper when we read scripture for application in “foreign” contexts. If we don’t, we may inadvertently “assume the gospel” by limiting ourselves to its legal framework without consideration of other 6 biblically faithful and culturally meaningful alternatives. Blindspots occur precisely where we imagine that our own understanding and presentation of the gospel are free of cultural influence. But every gospel presentation is shaped by the cultural values of the presenter and their perception of their intended audience’s cultural values.

Lesslie Newbigin famously states, “We must start with the basic fact that there is no such thing as a pure gospel if by that is meant something which is not embodied in a culture.”7 To be sure, the gospel transcends culture and its relevance is not confined to any one particular culture. However, this does not mean that we naturally understand and communicate that message apart from our own cultural vantage point, with its countless metaphors, assumptions, images, and analogies. No one person—and no one theology!—transcends all time and cultures.

WHAT ARE WE AFRAID OF?

I sometimes find people afraid to delve into honor/ shame, as if taking it seriously would undermine the guilt/ innocence dimension of the gospel or the objectivity of moral right and wrong as established in the Bible. Such impressions are quite mistaken.8 The acronym SCARE outlines five common fears people have about letting H/S substantially influence their theological and missiological thinking.

Slow

H/S concerns one’s entire view of the world. Therefore, we cannot expect to “get” H/S quickly. It touches on every aspect of life. Furthermore H/S ministry is holistic, aiming at life transformation. If missionaries are too focused on numerical growth (i.e. conversions), they will lack the patience to invest in relationships and the process required for long-term maturity (i.e. discipleship).

Complex

H/S is not a formula. Our worldview is more like a story than a system. H/S ministry cannot be reduced to four or five simple rules with guaranteed results. H/S feels complex because it integrates all of one’s life––head, heart and hands. However, ministry in the real world is complex (and not simply in so-called “honor-shame cultures”). Sometimes, we need to complicate our view of the problem if we are going to accurately solve it. For example, we wouldn’t tell cancer patients just to drink more water and get exercise. Similarly, if we want to minister in H/S cultures, we must wrestle with complexity.

Ambiguous

An H/S worldview understands that daily life is full of gray; not everything is black and white. The Bible does not give us clear commands regarding how we ought to behave in every context and relationship. It mostly tells stories from which we abstract principles based on our culture.

Paul struggled with the ambiguity surrounding food offered to idols (cf. Rom 14; 1 Cor 8–10). It is intriguing and humbling that, according to Paul, people can “honor the Lord” even as they act out of mistaken theology (i.e. “the one who is weak in faith”; Rom 14:1–6). Our grasp of what is right and true might vary by degree in different settings. Such ambiguity may frighten those who want to draw distinct, universally applicable lines in the moral sand.

Relativistic

Many people are conscious of sinful expressions of H/S (i.e. gang activity, honor killings, etc.). They fear that an H/S perspective opens the door to moral relativism. Yet Paul repeatedly explains sin in terms of “dishonoring” God and falling short of his glory (Rom 1:21–23; 2:23–24; 3:23). The gospel helps us more clearly apprehend God’s own standard for H/S. Several have detailed how H/S are critical themes in shaping a robust biblical theology.9

Error

Ultimately, some fear that H/S thinking leads to theological error. After all, if the Church’s greatest minds have not emphasized H/S, who are we to pave new ground? To make matters worse, (Westernized) systematic theology consistently avoids any discussion of H/S. This is not without irony, as Protestantism itself is a testimony to the fact that church tradition often creates “theological inertia” in need of correction. In fact, H/S is not “new”; it permeates Scripture and the cultures in which it was inspired. The problem lies in the fact that we inevitability read the Bible with cultural filters, then dichotomize and absolutize theological categories. As a result, we end up with nearly as many blindspots as Bartimaeus.

H/S should not “SCARE” people; it is a natural aspect of all human cultures, and especially “collectivistic” societies. Collectivism is woven into the fabric of God’s mission in the world. Christ’s church represents God’s human family, consisting of all nations. God made humanity for the sake of His glory. It is perfectly legitimate to say that God has “face” (i.e. glory),10 and that the gospel recounts how Christ “saves God’s face.”11

God’s people declare His glory (honor). Jesus himself explains faith in H/S terms: “How can you believe, when you receive glory from one another and do not seek the glory that comes from the only God?” (John 5:44, ESV). By neglecting H/S in our theology and ministry, we make it more difficult for multitudes to believe in Christ.

CONSEQUENCES OF OUR BLINDSPOT

Here are four consequences of our H/S blindspot, which I’ll address further in my forthcoming book, due out in January.12

First, anxieties about H/S may lead missionaries into practices that are counter-productive for long-term fruitfulness in H/S contexts. For example, people in traditional H/S cultures have a high respect for authority and tradition. We may confuse mere conformity to a teacher’s request with obedience resulting from a changed heart. Missionaries can also easily forget that many non- Westerners will pray a “prayer of salvation” simply to preserve friendships and save “face.”

Second, if we neglect to give attention to H/S, we are less likely to see worldview transformation. After all, H/S is a holistic concept, concerning every aspect of a person’s life. One’s identity transcends legal metaphors. The gospel transforms how we see God, ourselves, and others. It reshapes how we understand authority, reputation, and every human relationship.

Third, by overlooking the importance of H/S, missionaries unintentionally foster “theological syncretism.” We may be content with doctrines that our denomination, organization or church affirms but that may not reflect the emphasis of the original authors in their context. Yet, emphasis too is an integral part of the biblical authors’ meaning. Christians can easily “compromise the gospel by settling for truth.”13 Rather than elevating specific truths beyond their biblical emphasis, we must seek to understand the truths of God’s Word in balance with one another and not settle for pulling truths out of their context.

Without H/S, one’s theology can become abstract and less integrated. We can overemphasize systematic theology at the expense of biblical theology and exegesis. When this happens, Christian theology devolves into mere philosophy and we miss the grand narrative of scripture.

Finally, missionaries risk the danger of “judaizing” their listeners. That is, if missionaries do not remove this H/S blindspot from their own thinking, they will unconsciously present the gospel in a way that requires listeners to think like Westerners (e.g. as individualists who emphasize law) before they can understand the message and believe the gospel. Sadly, such new believers become functionally “Western” Christians even though they may culturally be African, Indian, Chinese, or Thai.

May God’s Word be a lamp unto our feet, exposing the blindspots that encumber gospel ministry.

comments