Core Issues and Interesting Characters

As outlined in several of the articles in this special issue, the Fuller School of World Mission was an amazing place 50 years ago. Space will not allow me to mention all the “core issues” or “characters” that were a part of the SWM back then. Other works detail that, such as Chuck Kraft’s book, SWM/SIS at Forty (WCL 2005).

Just before the school opened, Fuller promoted its new “Graduate School of World Mission,” which would:

- Prepare men to fulfill the Great Commission in the midst of change peculiar to our age.

- Provide a theology of missions for all seminary students looking toward a pastorate.

- Bring Christian nationals to the school as students and teachers to provide opportunities for mutual exchange.

- Develop a team of research specialists to study and provide a center of thought and information regarding World Mission.[1]

Donald A. McGavran and Alan Tippett moved to the School of World Mission together from the Institute of Church Growth in Oregon. Tippett’s strong background in anthropology added a crucial dimension and scholarship to McGavran’s passion for church growth.

As the SWM developed, the students themselves contributed much of the content of the learning. They were almost all field-experienced missionaries and were appropriately called “associates.” Faculty and associates would meet regularly just to discuss ideas, often totally unconnected to any particular assignment.

When asked by professors at other institutions how many students the SWM had, Ralph D. Winter, half joking, would reply, “four to five,” pause for a shocked reaction, and add, “but we have 100 teachers” (referring to the “associates.”) He would say he was not sure what the students learned, but he and the other faculty learned a great deal about the world where the associates had served as missionaries.

As other faculty were added, they would often meet evenings with the students, and two or three students would tell the story of the works with which they had been involved on the field. They would draw graphs and critique what they were doing. When students first arrived, McGavran would interview them for an hour or more, asking questions to learn about their part of the world. He wanted to learn and grow in his awareness of the world, not just his own fields of interest or experience.

Two “hot” issues of that day were Church Growth and the Homogeneous Unit Principle (HUP). As all the faculty would do to support each other, Ralph Winter wrote a chapter in McGavran’s book Crucial Issues in Missions Tomorrow. (Moody Press, 1972) challenging those who suggested the church growth movement was only, or mainly, interested in numbers. He wrote:

Those who emphasize “church growth” are sometimes accused of being more interested in quantities of church members than in their quality. This is despite the fact that the very phrase church growth implies an additional dimension of emphasis beyond conversion, since it focuses not on how many raise their hands at an evangelistic service but on the incorporation of the new believer into church life. Other religions may consist of individuals worshiping at shrines, but the essence of Christianity goes beyond individual experience. Thus, the very concept of church growth is an attempt to emphasize the quality of corporate life beyond the quantity of individual decisions. (175-176)

There were—and are—also those who disagree with the HUP, which was foundational to the church growth model. In the extreme, some felt that the HUP was racist—though that has been shown to be invalid. The misunderstanding or misinterpretation of HUP’s core idea often grows from those who desire an integrated church fellowship sooner than new believers may be ready for it. In his “breakout” book, The Bridges of God (World Dominion Press, 1955), McGavran hinted at the idea of spreading Christ to those groups that were on the fringe of an existing church, not merely spreading the message through more effective evangelism (however helpful and necessary that is). Embedded in the title The Bridges of God was the idea that a person who was from another culture, who expressed interest in the gospel and the things of God, was a bridge of God back to that people. Thus, HUP was a method for evangelistic growth, not a long-term approach for structuring a church.[2]

When he first arrived, one of Ralph Winter’s passions was Theological Education by Extension. At its core, TEE was seeking to get training out to recognized leaders in the church, rather than bringing them to distant locations away from the people they serve. Winter believed that the church in America was suffering and would continue to suffer if it could not deal with the issue of how leaders are trained for ministry here and internationally. He would often trace the history of the church in different places in the world, noting the problems created in churches when real local leaders were replaced with foreign, seminary-trained and ordained pastors, who were either not leaders in gifts or who were not recognized as such. This, he believed, was the major failure of the Student Volunteer Movement.

While models of TEE have shifted over the year, the emphasis has grown as modeled in the distance education methods used by many schools, especially for degree completion programs.[3] TEE was and still is very successful, even with the problems of distribution and quality inherent in the 1960s. There are still TEE programs in operation. India has the largest, called The Association for Theological Education by Extension TAFTEE. The seventh edition of the global prayer book, Operation World noted that in Africa, “TEE programmes, modular training and training-in-service are all key for training both lay leadership and the many overworked and bivocational pastors. Several hundred TEE programmes now operate in Africa, accounting for over 100,000 students. Despite past obstacles, TEE is establishing itself as an effective alternative for theological training.” (Biblica 2010, p 37)

While models of TEE have shifted over the year, the emphasis has grown as modeled in the distance education methods used by many schools, especially for degree completion programs.[3] TEE was and still is very successful, even with the problems of distribution and quality inherent in the 1960s. There are still TEE programs in operation. India has the largest, called The Association for Theological Education by Extension TAFTEE. The seventh edition of the global prayer book, Operation World noted that in Africa, “TEE programmes, modular training and training-in-service are all key for training both lay leadership and the many overworked and bivocational pastors. Several hundred TEE programmes now operate in Africa, accounting for over 100,000 students. Despite past obstacles, TEE is establishing itself as an effective alternative for theological training.” (Biblica 2010, p 37)

But Winter was more known at the SWM for teaching church history—though he never called it that. Because the associates (students) were generally mature missionaries and mission leaders, he engaged them in a number of subjects, which he saw as connected, even if the students did not. He shared his broad perspective on the “historical development of the Christian movement”—his early course title.

Here are some student reflections on what it was like to be in Winter’s classroom.

In the fall of 1966, Paul McKaughan was just off from his first four years in Brazil. Winter was not yet on full-time faculty.

No one really knew who Winter was at that point, except that he was involved with TEE in Guatemala, and that program was truly ground-breaking. Many of the older students were frustrated with Winter’s course because it was mostly the “Winterian” stream of consciousness that we all came to appreciate. There was a textbook, but we didn’t really follow it. Contrary to many of my more mature student colleagues, I was totally enthralled, because amid the rambling in each class was at least one scintillating original idea or insight that I had never heard anyone express before those classes.[4]

Like other students who were studying at Fuller’s School of Theology, Bob Blincoe was required to take one course in the SWM. Having been a history major at the University of Oregon, he decided to take a history class, and chose Winter’s January 1976 course on the Expansion of Christianity:

In his first lecture he picked up the chalk and drew the cross of Christ in the middle of the blackboard. He said, “Let’s not start the history of Christianity in 32 A.D.” He walked to the farthest left hand corner of the blackboard, which stretched across the entire wall behind him, and he said, “Let’s start with Abraham.” And he wrote the year 2000 B.C. on the blackboard. “What is this!” I thought. Then Dr. Winter made the connection between Abraham and Jesus Christ’s Great Commission, and then he connected all the history of the Bible and all of the Psalms into one unity of the Bible, “I will bless you and you will be a blessing to all the families of the earth.” I had never heard of the Bible as a single story, and never heard anyone suggest a unity based on the Great Commission that began with God’s call to Abraham, “blessed to be a blessing.” Then Dr. Winter said, “This course is about what God did with the Bible in history.”

One off-hand comment he made was that “no one’s education is complete until they have spent two years living in another culture.” Oh, no! I thought: I’ve been in school already for 18 years, and now I have to admit that I know nothing about other cultures. The result of this was that I and my bride, Jan…spent two years in Thailand.

He was first of all a teacher, the best I ever had, and endlessly patient with his students.[5]

After serving in Thailand, Bob was a pastor in rural California. Then, Winter recruited Bob to serve at the U.S. Center for World Mission (now Frontier Ventures). Bob did so, on his way to serve in Iraq. He continues to serve in top leadership of a mission agency.

Of course, Winter is best known for the plenary presentation he gave at Lausanne in 1974. It was given just two years before Ralph and Roberta, his wife, left the SWM and started the U.S. Center for World Mission. The needs of the unreached peoples (cultures) of the world drew them to start a community that would focus on the places needing breakthroughs at the edges of the Kingdom.

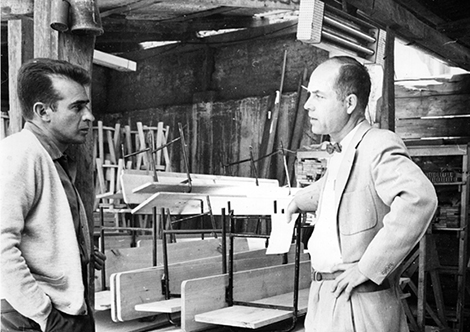

Photo: Dr. Ralph Winter in Guatamala

This article is slightly modified from the text that can be found in the book, Ralph D. Winter, Early Life and Core Missiology by Greg H. Parsons. WCIU Press, 2012.

[1] The Bulletin of Fuller Theological Seminary, Spring 1965, 1, 3.

[2] For more on the current HUP debate and other issues related to Winter, see Parsons, Greg. “Will the Earth Hear His Voice? Is Ralph D. Winter’s Idea Still Valid?” International Journal of Frontier Missiology 32, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 5-18.

[3] In 2008, Ross Kinsler worked with Winter in Guatemala on TEE, and published the book Diversified Theological Education: Equipping All God’s People that included articles from experts in this kind of training in different parts of the world. (Kinsler 2008)

[4] Email from Paul McKaughan to the author, Sept. 6, 2010.

[5] Email from Bob Blincoe to the author on August 31, 2010, 1-2.

comments