Why Communicate the Gospel Through Stories

From Reconnecting God’s Story to Ministry: Cross-cultural Storytelling at Home and Abroad, 2005. Used by permission of William Carey Library, Pasadena, CA

I thought that I had finally learned enough of the Ifugao language and culture (Philippines) to allow me to do some public evangelism. I developed Bible lessons that followed the topical outline we received in pre-field training: the Bible, God, Satan, humanity, sin, judgment and Jesus Christ. I began by introducing my Ifugao listeners to the authority-base (the Bible). Then I quickly moved on to the second part of the outline (God), and so forth, culminating with Jesus Christ. I presented the lessons in a topical, systematic format. My goal was not only to communicate the gospel, but to communicate it in such a way that the Ifugao could effectively articulate it to others.

But as I taught, I soon realized that the Ifugao found it difficult to follow the topical presentations and found it even harder to explain the content to others. I was perplexed. Something needed to change, so I added a number of stories from the Old Testament to illustrate the abstract (theoretical) concepts in the lessons through pictorial (concrete) characters and objects. I told stories about Creation, the Fall, Cain and Abel, the Flood, the escape from Egypt, the giving of the Ten Commandments, the Tabernacle, Elijah and Baal, all of which would provide foundation for Jesus’ story. Their response was phenomenal. Not only did the evangelistic sessions come alive, the recipients became instant evangelists, telling the stories to friends enthusiastically and effectively. From then on I integrated stories in all my evangelistic efforts.

Back to the Power of Story

Back to the Power of Story

After the Ifugao reintroduced me to the power of story, I began to research the topic.1 I soon discovered that many disciplines, including management, mental and physical health, apologetics, theology and anthropology rely heavily on telling stories.

Sadly, though, storytelling has become a lost art for many Christian workers in relation to evangelism. Few present the gospel using Old Testament stories to lay a solid foundation for understanding the life of Christ, or connect these stories of hope to the target audience’s story of hopelessness. Rather, many prefer to outline four or five spiritual laws and prove the validity of each through finely honed arguments.

A number of hollow myths bias this preference against storytelling in evangelism:

(1) stories are for children; (2) stories are for entertainment; (3) adults prefer sophisticated objective, propositional thinking; (4) character derives from dogmas, creeds and theology; (5) storytelling is a waste of time in that it fails to get to the more meaty issues. As a result of these and other related myths, many Christian workers have set aside storytelling. To help reconnect God’s story to evangelism-discipleship, I will highlight seven reasons why storytelling should become a skill practiced by all who communicate the gospel.

1. Storytelling is a Universal Form of Communication

No matter where you travel in this world, you will find that people love to tell and listen to stories. Young children, teenagers and seniors all love to enter the life experiences of others through stories.

Whatever the topic discussed, stories become an integral part of the dialogue. Stories are used to argue a point, interject humor, illustrate a key insight, comfort a despondent friend, challenge the champion or simply pass the time of day. No matter what its use, a story has a unique way of finding its way into a conversation.

Stories can be heard anywhere. They are appropriate in churches and prison, in the court house and around

a campfire.

Not only do all people tell stories, they have a need to do so. This leads us to the second reason for storytelling.

2. More than Half of the World’s Population Prefer the Concrete Mode of Learning

Illiterate and semi-literate people in the world probably outnumber people who can read.2

People with such backgrounds tend to express themselves more through concrete forms (story and symbol) than abstract concepts (propositional thinking and philosophy).

A growing number of Americans prefer the concrete mode of communication. This is due, at least in part, to a major shift in communication preference. One of the reasons behind this shift (and the dropping literacy rate) is the television. With the average TV sound byte now around 13 seconds, and the average image length less than three seconds (often without linear logic), it is no wonder that those under its daily influence have little time or desire for reading. Consequently, newspaper businesses continue to dwindle while video production companies proliferate. If Christian workers rely too heavily on abstract, literary foundations for evangelism and teaching, two-thirds of the world may turn its attention elsewhere.3

3. Stories Connect with Our Imagination and Emotions

Effective communication touches not only the mind, but also reaches the seat of emotions—the heart. Unlike principles, precepts and propositions, stories take us on an open-ended journey that touches the whole person.

While stories provide dates, times, places, names and chronologies, they simultaneously provoke tears, cheers, fear, anger, confidence, conviction, sarcasm, despair and hope. Stories draw listeners into the lives of the characters. Listeners (participants) not only hear what happened to such characters; through the imagination they vicariously enter the experience. Herbert Schneidau eloquently captures this point when he states: “Stories have a way of tapping those feelings that we habitually anesthetize.”4

People appreciate stories because they mirror their own lives, weaving together fact and feeling. Stories unleash the imagination, making learning an exciting, life-changing experience.

4. Approximately 75% of the Bible is Story

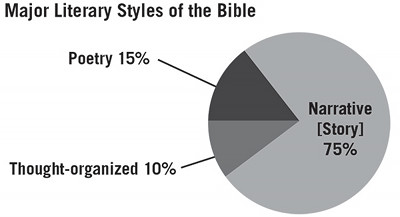

Three basic styles of literature dominate the landscape of the Scriptures—story, poetry and thought-organized format—but story is predominant (see figure above).

Over the centuries, the writers of the Bible documented a host of characters: from kings to slaves, from those who followed God to those who lived for personal gain. Such stories serve as mirrors to reflect our own perspective of life, and more importantly, God’s. Charles Koller astutely points out:

The Bible was not given to reveal the lives of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, but to reveal the hand of God in the lives of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; not as a revelation of Mary and Martha and Lazarus, but as a revelation of the Savior of Mary and Martha and Lazarus.5

Poetry covers approximately 15% of the Bible. Songs, lamentations and proverbs provide readers and listeners with a variety of avenues to express and experience deep emotions. These portions of Scripture demonstrate the feeling side of people, and illuminate the feelings of God as well.

Poetry covers approximately 15% of the Bible. Songs, lamentations and proverbs provide readers and listeners with a variety of avenues to express and experience deep emotions. These portions of Scripture demonstrate the feeling side of people, and illuminate the feelings of God as well.

The remaining 10% of the Bible is composed in a thought-organized format. The apostle Paul’s Greek-influenced writings fall under this category, where logical, linear thinking tends to dominate. Many Westerners schooled in the tradition of the Greeks, myself included, prefer to spend the majority of time in the Scripture’s smallest literary style. Yet if God communicated the majority of his message to the world through story, what does this suggest to Christian workers?

5. Every Major Religion Uses Stories to Socialize its Young, Convert Potential Followers and Indoctrinate Members

Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Christianity—all use stories to expand and limit membership, and assure ongoing generational adherence. They use stories to differentiate true members from false, acceptable behavior from unacceptable. Stories create committed communities.

Whether Paul was evangelizing Jews or Gentiles, the audience heard relevant stories. Unbelieving Jews heard about cultural heroes, such as Abraham, Moses and David (Acts 13:13-43). Unbelieving Gentiles heard about the powerful God behind the creation story (Acts 14:8-18; 17:16-34). Maturing believers heard the same stories with a different emphasis.

Could one of the reasons for this be that stories provide an inoffensive, non-threatening way of challenging one’s basic beliefs and behavior?

6. Stories Create Instant Evangelists

People find it easy to repeat a good story. Whether the story centers around juicy gossip or the gospel of Jesus Christ, something within each of us wants to hear and tell such stories. Suppressing a good story is like resisting a jar full of your favorite cookies. Sooner or later, the urge is too strong and the cookie gets eaten, the story gets told. Told stories get retold.

People find it easy to repeat a good story. Whether the story centers around juicy gossip or the gospel of Jesus Christ, something within each of us wants to hear and tell such stories. Suppressing a good story is like resisting a jar full of your favorite cookies. Sooner or later, the urge is too strong and the cookie gets eaten, the story gets told. Told stories get retold.

Because my Ifugao friends could relate well to the life-experiences of Bible characters, they not only applied the stories to their lives, they immediately retold them to family and friends, even before they switched faith allegiance to Jesus Christ. Stories create storytellers.

7. Jesus Taught Theology through Stories

Jesus never wrote a book on systematic theology, yet he taught theology wherever he went. As a holistic thinker, Jesus often used parabolic stories to tease audiences into reflecting on new ways of thinking about life.

As Jesus’ listeners wrestled with new concepts introduced through parables, they were challenged to examine traditions, form new images of God, and transform their behavior. Stories pushed the people to encounter God and change. It wasn’t comfortable to rise to the challenge of Jesus’ stories-—to step out of the boat, turn from family members, extend mercy to others, search for hidden objects and donate material goods and wealth to the poor—none of it was inviting. But the stories had thrown open possibilities that made it difficult to remain content with life as it had been. Whichever direction the listeners took, they found no middle ground. They had met God. Jesus’ stories, packed with theology, caused reason, imagination and emotions to collide, demanding a change of allegiance.

Conclusion

The Bible begins with the story of creation and ends with a vision of God’s recreation. Peppered generously between alpha and omega are a host of other stories. While stories dominate Scripture, they rarely enter the Christian worker’s strategies. Leland Ryken cogently asks:

Why does the Bible contain so many stories? Is it possible that stories reveal some truths and experiences in a way that no other literary form does—and if so, what are they? What is the difference in our picture of God when we read stories in which God acts, as compared with theological statements about the nature of God? What does the Bible communicate through our imagination that it does not communicate through our reason? If the Bible uses the imagination as one way of communicating truth, should we not show an identical confidence in the power of the imagination to convey religious truth? If so, would a good starting point be to respect the story quality of the Bible in our exposition of it?6

Is it not time for today’s Christian workers to revitalize one of the world’s oldest, most universal and powerful art forms—storytelling? I believe so. I also believe that Christian workers, with training and practice, can effectively communicate the finished story of Jesus Christ and connect it to the target audience’s unfinished story. Presenting an overview of Old and New Testament stories that unveils the history of redemption will highlight for the listeners the Storyline (Jesus Christ) of the sacred Storybook (Bible). Should this happen, the gospel will be much more easily understood, and more frequently communicated to family and friends.

Transforming Worldviews through the Biblical Story

By D. Bruce Graham

The Bible reveals a story. Its earliest chapters trace the history of the people of Israel; it was written to help them understand their unique identity and purpose as a people. Their identity was rooted back in the first human family and the God of Creation who was fulfilling a purpose on earth through them. But Israel is not unique in this sense.

Every nation needs to understand its history and origins. People tell and re-tell their stories, which shape their worldview and identity as a people. But a people’s story that is disconnected from God’s story will remain hopeless and without enduring purpose. People need to find their place and purpose on earth in light of God’s story among the nations.

People filter new information through the grid of their worldview and evaluate it accordingly. In the beginning of the movie The Gods Must Be Crazy, a glass Coke bottle is dropped out of a small airplane flying over the Kalahari Desert. It lands among the Sho desert people and awakens intense curiosity. Wondering why the gods have sent this strange tool, they spend several days evaluating its usefulness. Finally the elders conclude that this new thing is not good for them, and they set out to dispose of it.

The biblical story is processed in a similar way by people who hear it for the first time. They ask themselves, “Is this good for us? Does it give us a better way of coping with our world, of making sense of it? Does this story match reality as we know it? Does it give hope to our people?” For the biblical story to be received and believed by a people, it must find a place and connection within their worldview. If it is perceived as a story that has answers for their people, as a story that fulfills the longings and hopes of their people, it becomes good news to them. They can see themselves connected in a new way to an ancient and holy God who has great concern for them. He has revealed himself to them in his Son who fulfills ancient promises and hopes for every nation. Following him restores their identity and purpose on earth. They become part of God’s story.

This kind of worldview transformation requires storytellers who grasp the whole biblical story and can meaningfully communicate it among a people. This is far from bringing a people a new “religion.” It’s far more than a way to “get people saved.” It does not extract a people into a foreign community. A skilled biblical storyteller engages a people in a process of discovery that does not disregard their own story, but rather gives them new perspective and new purpose in connection with God’s purpose.

Working in India as a teacher of missionary candidates, I observed students learning the Bible by memorizing its details—authors, dates, names of people and places, etc. They learned facts about the Bible and could teach biblical truths. While people sometimes responded without foundation in the biblical story, they easily turned to another teaching or another god if something more interesting came along that would meet their perceived need.

But something new began to develop among my students when we started going through the whole biblical story. We approached it inductively, seeking to discover God’s message within each story. How were the stories connected? What was at the heart of the whole story? Their worldview and perspective began to change. They felt part of what we called the “Seed-Man Mission” (the term we used to describe the heart of the story from Gen 3:15). They were energized and felt part of something significant.

But knowing the story did not necessarily make them good storytellers. They had to practice telling the story. And they had to understand the people they wanted to reach in order to effectively communicate the biblical story. Rather than reading books about the people (usually written by outsiders), we encouraged the students to study the people inductively. They spent time in teashops and homes, discovering the concerns and interests of the local people. They took part in their celebrations and traditions, always asking God for insight and wisdom that would help them tell the biblical story most effectively.

This led to creative ways of communicating the story—song, drama, pictures or simply storytelling, are all common forms of expression among Indians. One student drew pictures of successive stories through the Bible, one page per story, and hung them on his living room wall. Another invited friends to his home for discussion weekly and eventually had religious leaders going through the whole biblical story. One woman spent months, even years, listening to the stories and concerns of the Muslim women among whom she worked. Eventually they began to open up to her, and she had biblical stories to share with them that captured their interest. They wanted to hear more.

So, let’s multiply storytellers who understand the whole story. Let’s help them internalize it for themselves inductively so this story becomes their story. Let’s encourage them to take the time to know the local people and their stories so they meaningfuly connect that peoples’ story with God’s story. This will transform a people's worldview.

comments