From the Guest Editor

Learning From My Own Mistakes

They were not Hearing

Over a decade ago, I was traveling through Mozambique speaking to an audience that had traveled some distance. While preaching through a portion of Nehemiah, I noticed many were falling asleep during point one of my expository preaching. So I changed my mode of delivery and also leaned into the microphone. There was a momentary jolt, but most managed to fall asleep again prior to point two in the exposition! My conceptual—linear—textual Gutenberg methodology shattered at the brick wall of oral cultures. My communication method was ineffective.

After the trip, I was determined to find out why the audience was not listening. This sojourn of discovery radically altered my thinking and sent me on a journey of exploring the world of oral preference learners and oral communicators; I became convinced that we were missing the mark of reaching oral learners and unreached people groups.

In the middle of the last decade, we witnessed the embryonic releases of social media and networks, and we are now participating in the maturing digital social networks. The Zuckerberg generation and its apps have cajoled, encouraged, and tethered us into a narcissistic, instantaneous, conversational environment.

From Gutenberg to Zuckerberg, the global resurgence of orality has arrived with vigor, and has tectonic implications

for our stewardship of the gospel for this century.

The Seven Disciplines of Orality

Orality is defined in Webster’s New World College Dictionary (2009) as:

- a reliance on spoken, rather than written, language for communication

- the fact or quality of being communicated orally

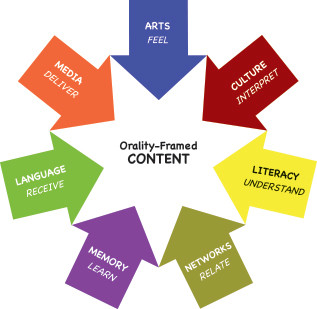

For our purposes in missions, orality, as described by Charles Madinger, is “a complex of how oral cultures best receive, process, remember and replicate (pass on) news, important information, and truths.”1 Approximately 80%2 of the world’s population cannot or will not hear our message when we communicate it to them in literate ways and means.3 The phrase “ways and means” denotes that there are resources (ways) we have of packaging our message, and methods (means) of delivering it.4

Madinger further elucidates:

Our resources (ways) for our programs come in the content we develop to reach people with the good news or help them grow in it. That content must connect with the real needs of the audience and how the Word applies to those needs from their perspective. The seven descriptive disciplines of orality lead us to package the message better with cultural sensitivities, put it in terms to which the audience can relate and understand, and use mnemonic tools to make sure the truth sticks. We deliver the message through locally practiced arts, by networks of trusted relationships, and media forms that reach as far as we can and as deeply as possible.5

Our resources (ways) for our programs come in the content we develop to reach people with the good news or help them grow in it. That content must connect with the real needs of the audience and how the Word applies to those needs from their perspective. The seven descriptive disciplines of orality lead us to package the message better with cultural sensitivities, put it in terms to which the audience can relate and understand, and use mnemonic tools to make sure the truth sticks. We deliver the message through locally practiced arts, by networks of trusted relationships, and media forms that reach as far as we can and as deeply as possible.5

Many people equate “storytelling” with “orality”, but this is just one of the disciplines—that of the Arts—within the Seven Disciplines of Orality. Or erroneously, some people tend to think orality is for people who are illiterate, but we have discovered through solid academic research that 80% of the world’s populations are oral preference learners! Now with the pull towards oral-visual media, our framing of the content of our message must change, and our distribution and application of messages must be tailored accordingly for the digitoral generation.

Orality Applied Across Multiple Domains and Sectors Across the Globe

All of the writers of articles in this issue of Missions Frontiers are seasoned practitioners of orality, influencers within their own organizations, and collaborators across ministry and cultural boundaries. There are two bookends for this issue of MF (with intentional pun and imagination on bookends as we move from textual transmission societies into digitoral relationally rooted cultures). Chuck Madinger anchors one bookend with a fresh look at what orality is and is not, and its application into different countries; Bauta Motty and Sung Bauta complement the article with an examination of how orality works

in the context of HIV/AIDS and amongst widows.

Mark Overstreet provides an overview of how orality works in church planting; Laura Macias looks at how the arts are appreciated within oral cultures. God is blowing a new wind among Muslims. David Garrison’s new, insightful book, A Wind in the House of Islam,6 talks about giving voice to those who have stepped away from Islam and became followers of Christ. John B provides that voice through a case study on how orality is applied to establishing a community of Christian witness, and how they are spreading the Word into other groups.

Organizations and denominations that have embraced orality are generally highly relational. They seldom go it alone and they value collaboration highly. Joe Handley provides a look at how collaboration works among indigenous leaders. Marlene Lefever looks at how collaboration works within her large organization and how it works cross-culturally with other organizations. Jim Rosene and Brian Rhodes talk about how two Western agencies came together with a focus on orality strategies and projects to serve the Church in DR Congo. Vicky Marie writes on how orality is used in pioneering business planting.

This century is paced by an oral-visual speed that numbs the mind. New generations are reading less and “listening” more through devices, and they are consuming visual media as if it were a regular food group. Lori Koch and David Swarr provide color on a previously published declaration that had foresight for this new generation, and this is complemented with an article on how to reach the Bible-less peoples. Carol and Calvin Conkey look at how visual media is both necessary and impacting nations. And with a continuation on both collaboration and visual media, we add David Palusky’s article on technology and distribution. Mr. Palusky and I are dreaming of using drones for distribution of content in difficult to reach areas.

The other bookend anchor is Bill Bjoraker’s significant review of an important book, Saving God’s Face, by Jackson Wu. Since orality has to do with framing of the content, then, how do cultures frame the Bible and how does the supremacy of the Bible interact with cultures? With the post-modern societies vacating a guilt-innocence framework and fully embracing an honor-shame worldview, we see this generation, and indeed this century, returning to the worldview of the time of Christ, which was and still is anchored in an honor-shame worldview, a context in which the Bible was given in both oral and written form.

A Little Peering

Seemingly, God is allowing the orality movement to gain both traction and momentum. Among Bible Translation organizations, some have declared that every new translation shall commence with oral stories from the Bible in the heart language of the people. Theological educators and institutions are embracing orality. The outlines of dreams, visions, and directions are taking shape for this decade and century. People are deeply passionate about the causes of orality! As of this writing, Ed Weaver of T4Global is planning to ride his bicycle 4,000 miles diagonally across the USA to bring awareness to orality, oral culture, and oral learners. Also as of this writing, plans are underway to establish the Center for Oral Scripture in the Middle East.

The task of world mission is not about numbers, triumphalism, and checklists. The task of world mission involves this generation, a generation of “exiles” seeking the welfare of the cities and communities, to bring forth the gospel with reflection, care, and love to reach the least, the last and the lost! Come and join the orality movement!

comments