Hitting the Mark

“Indigenous Movements Everywhere”

There are at least two ways in which I think the mission community has strayed from adequately evaluating our essential goal of reaching people groups and seeing indigenous movements everywhere.

First, we have treated engagement as an end goal rather than an essential step toward such movements.

Second, we have used metrics that do not clearly reveal where such movements are lacking.

IMB is in the process of refining critical success factors to evaluate our efforts to multiply disciples and churches within unreached peoples and places. We want to see movements! However, our desire for movements has not been clear in our engagement definition, and we have relied too heavily on metrics to evaluate whether a people group is reached. We have inherited and reinforced the metrics referred to in the second point as if metrics alone could determine whether or not a people group is reached. Additionally, we say that a people group is engaged when there is a church planting strategy (consistent with evangelical faith and practice) underway, but we have not been clear that the goal of engagement is a movement. For the record, the goal of engagement is reaching a people group through indigenous teams of capable leaders multiplying generations of disciples and churches in a sustained movement to Christ.

Movements are the work of the Holy Spirit, often in cooperation with human catalysts, flowing through relational networks that lead to a rapid succession of generations of households following Jesus. The rate of rapid succession varies, but it exceeds population growth and incremental Church Planting. Movements are how peoples both become and remain reached.

Where the fruit of past movements remains, such as in “post-Christian” peoples in Europe, the potential for the spread of the gospel today is greater than in peoples who have never been reached. After all, these people groups have Christian resources available to them. The Protestant Reformation, the Great Awakening and other historic revivals illustrate this potential for Europe today. The “Jesus Movement” of the late ’60s and early ’70s gives those of us old enough to recall it a basis for understanding the potential for such renewal movements in peoples once considered reached.

We have to be clear in our definition of engagement that church planters are not sent to plant a single church or even churches in succession. Donald McGavran pointed out in 1982[1] that the common Western approach to “planting a church” inhibits movements rather than encourages them. It is not enough to plant a church and hope God will initiate a movement. To collaborate with the Holy Spirit in launching movements, we must pursue God for generations of reproducing disciples and churches and teach them to reproduce by obeying all that Jesus commanded.

Additionally, some people groups have only one team among millions of people. These teams must raise up capable indigenous leaders who can engage substantial population segments of their own people group in order for a movement to occur.

What is the minimum size of a community of believing Christians able to pursue God for a movement? In Acts 2 we see the Holy Spirit initiate a movement through just 120 believers obeying Jesus’ command to wait for the Father’s promised gift. So an indigenous community of obedient Christians does not have to reach even 1% for a movement to be birthed. However it can take a few years for the start of a movement to mature through multiple generations resulting in what Luke recorded in Acts 19:10: “all the Jews and Greeks who lived in the province of Asia heard the word of the Lord.” Essential to such growth was the obedience of Paul and others to Jesus’ model, with baptism, acknowledging personal faith in Jesus Christ as the sole provision for salvation and with the Holy Spirit providing conversion and regeneration.

While engagement is a necessary step in reaching people groups, I think our focus on engaging every people group with one or two teams has contributed to the difficulty that these same teams have in securing additional teams. Think about it—once a UUPG is engaged, it is no longer on the UUPG list.

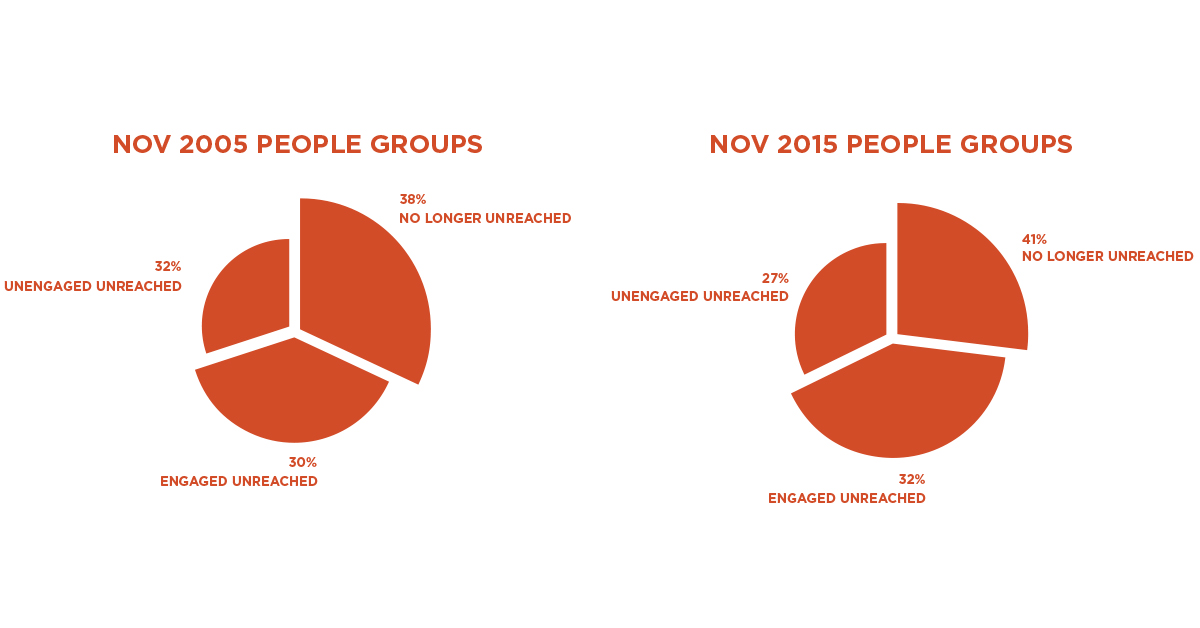

Let’s take a look at a breakdown of the world’s peoples by separating them into three categories: No Longer Unreached, Engaged Unreached, and Unengaged Unreached. We will look at two snapshots from IMB statistics—one from 2005 and one from 2015.

The two graphs above show that during the last ten years, the number of UUPGs has decreased from 32% to 27% of the world’s people groups. Great! Our engagement strategy is working.

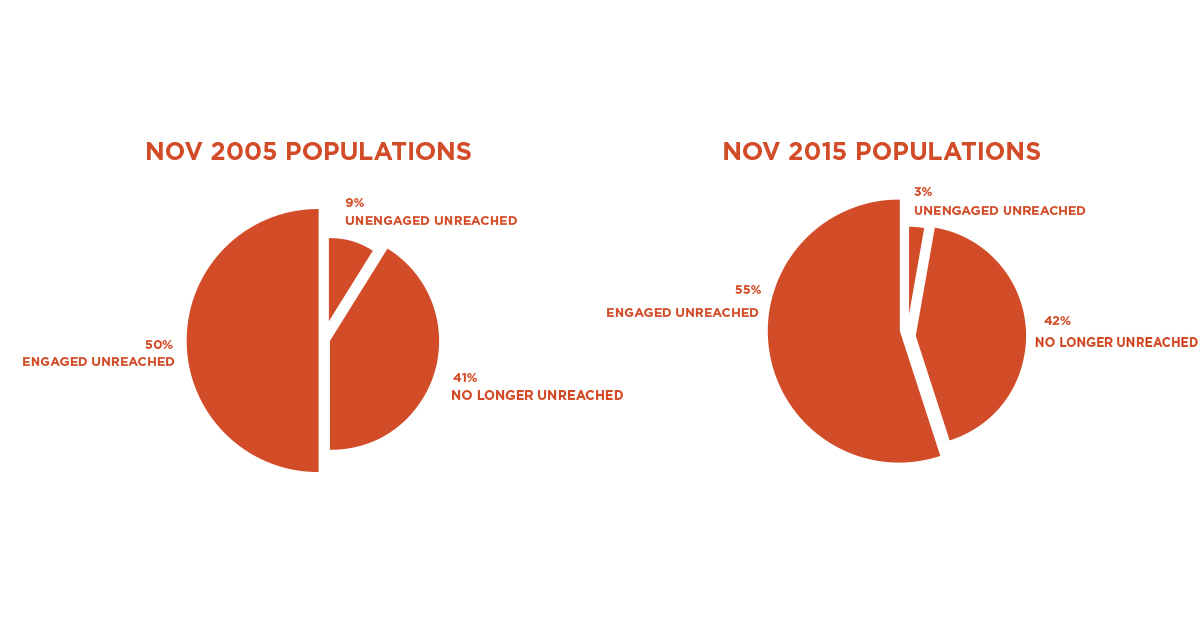

Now, let’s take a look at a breakdown of populations for these same three categories.

When we look at populations, we see that the population of UUPGs has decreased from 9% of the world’s population in 2005 to 3% of the world’s population in 2015, even more than the percentage decrease in the number of UUPGs. This is because those engaging UUPGs in the last ten years have focused on engaging the larger UUPGs. This means that the remaining UUPGs are significantly smaller than they were in 2005.

While the population of UUPGs has decreased from 9% in 2005 to 3% in 2015, the percentage of the world’s population living in engaged UPGs has increased from 50% to 55% and the average size of engaged UPGs is larger. We can infer from this trend that if we continue to pursue smaller and smaller UUPGs, we will do so at the expense of vast unengaged population segments of minimally engaged UPGs—consider India, for example, where many huge people groups have only one or two teams.

Finally, during the last 10 years the percentage of the world’s population living in people groups no longer unreached has increased by only one percent (from 41% to 42%).

There can be only one conclusion—we are far more successful in engaging than reaching. We need teams that will engage effectively—pioneering teams, engaging in the local language for the long-haul— with methodologies consistent with seeing movements occur.[2] Without this, we will continue to engage but seldom reach.[3]

There is a second way that I think we’ve strayed from the ultimate goal of establishing indigenous communities of reproducing churches and followers in every people group. I think we have relied too heavily on metrics to evaluate whether people groups are reached, and in this, we have set metrics above the essentials of reaching people groups.

How is “Unreached People Group” defined today?

According to Joshua Project, an unreached or least-reached people is a people group among which there is no indigenous community of believing Christians with adequate numbers and resources to evangelize this people group.[4] The original Joshua Project editorial committee selected the criteria as less than or equal to 2% Evangelical Christian and less than or equal to 5% Professing Christians.[5]

Alternately, according to IMB, an unreached people group is a people group with no indigenous community of believing Christians able to engage this people group with church planting. Technically speaking, the percentage of Evangelical Christians in this people group is less than 2 percent.[6]

While both definitions share certain essentials necessary for reaching people groups, the various metrics they produce are what are actually used by Joshua Project and IMB to determine whether a people group is unreached. For example, IMB shows the French in France as less than 2% evangelical (unreached), but there are reports of new house churches planted each week. IMB’s website, peoplegroups.org, shows that there is widespread church planting among this people group. Metrics alone should not be used to evaluate whether a people group is reached. It’s time to embrace a model which considers the qualitative essentials of what it means to reach a people group.

How was “Unreached People Group” defined in the past?

I recommend to the reader two important chapters in Reaching the Unreached—The Old-New Challenge, edited by Harvie M. Conn, Professor of Missions at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia in 1984. In the book, Ralph Winter offers an insightful perspective on the development and increasing momentum of the concept of “unreached people groups” in the early days of the Lausanne Movement. Let’s look at a few definitions from milestone meetings cited by Winter in Conn’s book. In these, the reader will see the struggle for both the quantitative and qualitative measures within the developing concept of “unreached.”

1974, Lausanne—“In the explanatory introduction of the Unreached Peoples Directory passed out at the congress, the definition of ‘unreached people,’ is not firmly established. Mentioned are both the 20-percent figure[7] and the phrase, ‘[where] there is no appreciable [recognized] church body effectively communicating the message within the unit itself.’”

1977, following Lausanne—“An unreached people group is a group that is less than 20% practicing Christian.”[8]

1978—Coleman and Winter introduced the concept of Hidden Peoples. “Hidden” is used because of our blindness to people groups. The concept as Winter defined it suggested that a Hidden People Group be defined as “any linguistic, cultural or sociological group defined in terms of its preliminary affinity (no secondary or trivial affinities), which cannot be won by E-1[9] methods and drawn into an existing fellowship.”

1988—A great deal of confusion remained and the 20% benchmark continued to be reinforced in Edinburgh and Pattaya. However, people using percentages in the definition began to admit that the best percentages could offer was a predictive approach to assessing whether a people group was likely to be reached. I salute Coleman and Winter because their concept defined “hidden” (unreached) by something other than a number or percentage—rather, an indigenous effort bringing new believers into existing fellowships.

1982, Chicago—At this meeting Unreached People was defined as “a group among which there is no indigenous community of believing Christians able to evangelize this people group.” It was in Chicago that the 20% practicing Christian benchmark was dropped in favor of the qualitative description of an unreached people group.

I can’t go further here to explore the history of the term or why we returned to metrics for predicting “unreached” status after 1980, but it is important to note that with the number of teams in our networks today, we have a new opportunity to return to qualitative measures important to establishing indigenous movements.

How will we measure what we want to see in the future?

First, let’s measure what we want to see happen. Look back over the words I have highlighted in bold print. These important concepts need to shape what we are after when it comes to reaching people groups.

Second, to make sure we get beyond engagement to actually reaching people groups, let’s join together in suggesting essentials for classifying a people group as no longer unreached.

Third, to make sure we critically monitor progress among people groups and other entities we engage, let’s create a continuum, similar to the Engel Scale[10] that helps us track progress from no awareness of the gospel to indigenous movements and partners in the Great Commission.

[1] Donald McGavran, Mission Frontiers, (Nov/Dec 1997), “A Church for Every People: Plain Talk About a Difficult Subject.”, pp. 13-16

[2] See Article by Jeff Liverman in Mission Frontiers, (Nov/Dec 2006), “What Does It Mean to Effectively ‘Engage” a People?”

[3] See Editorial by Robby Butler in Mission Frontiers, (Jan/Feb 2016), “Winning or Losing?”

[4] All bold characters are writer’s emphases.

[5] joshuaproject.net/help/definitions. Note: Joshua Project uses the terms “unreached” and “least-reached” to mean the same thing. The terms are used interchangeably on this website.

[6] http://www.peoplegroups.org/ Note:. Engagement means that a church planting strategy, consistent with evangelical faith and practice, is under implementation.

[7] In other words, the first hint of a definition was that an “unreached people group” is one that is less than 20% Christian. According to Winter, Ed Pentecost brought the 20% into the light while working with MARC as the research coordinator for the unreached peoples study presented at Lausanne in 1974. (Conn, p. 30)

[8] In 1977 the 20% criterion suggested in the MARC Directory was changed to this definition substituting practicing Christian for appreciable church body. However, the 20% criteria was too high because it meant that almost every people group was unreached. (Conn, p. 31)

[9] E-1 methods refer to a people group which has the capacity to win those of their own people group to Christ. (Conn, p. 32)

[10] Engel, J. F., & Norton, H. W. (1975). What’s gone wrong with the harvest?: a communication strategy for the church and world evangelization. Grand Rapids, Zondervan Pub. House, page 45.

comments