A “Fuller” Vision of God’s Mission and Theological Education

in the New Context of Global Christianity

When SWM Was Founded…

The School of World Mission (SWM) was established in 1965--during a significant period for global Christianity. The steady southwest-ward move since the 16th century gained serious southward momentum in 1950.[1] This was, without doubt, caused by the growth of African Christianity, especially its indigenous or independent families. Equally evident is a strong eastward pull from this period, accelerated two decades later (1970) by the growth of Christianity in Asia. This move has been steadily sustained until now, and is expected to continue in the foreseeable future. Unfortunately, we all know that this drastic development reflects not only “growth” in the geographical south and the east, but also “slowth” in the north and the west.[2] There is no doubt that SWM has sailed on this unique “trade wind,” although it was not always predictable and smooth.

Therefore, it is almost natural for the first Evangelical school dedicated to world mission to be exclusively focused on the expansion of global Christianity as its top priority. One of the two motivations, as observed by Charles Kraft, was the sharp focus on evangelism and church growth, which mainline (or conciliar) churches and their institutions had abandoned.[3] In an age when the missionary movement was losing its appeal especially among mainline churches as an imperialistic and colonial enterprise, Fuller’s commitment to intentionally begin SWM was a historic decision. McGavran’s missional optimism, that the missionary sun was not setting but rising, provided inspiration and motivation.[4] This conviction, coupled with a commitment to “workable mission knowledge,” made the institution more than a wind chaser: it now set the agenda and direction of Christian mission. The opening of numerous schools of mission and evangelism in the ensuing decades, both in North America and throughout the world, attests to the prophetic foresight and trend-setting mission leadership of the institution.

Therefore, it is almost natural for the first Evangelical school dedicated to world mission to be exclusively focused on the expansion of global Christianity as its top priority. One of the two motivations, as observed by Charles Kraft, was the sharp focus on evangelism and church growth, which mainline (or conciliar) churches and their institutions had abandoned.[3] In an age when the missionary movement was losing its appeal especially among mainline churches as an imperialistic and colonial enterprise, Fuller’s commitment to intentionally begin SWM was a historic decision. McGavran’s missional optimism, that the missionary sun was not setting but rising, provided inspiration and motivation.[4] This conviction, coupled with a commitment to “workable mission knowledge,” made the institution more than a wind chaser: it now set the agenda and direction of Christian mission. The opening of numerous schools of mission and evangelism in the ensuing decades, both in North America and throughout the world, attests to the prophetic foresight and trend-setting mission leadership of the institution.

This small but burgeoning institution was preoccupied by the urgent task of world evangelization. As Evangelicals, its faculty members must have felt a historic call to inherit this missionary mantle, so prominent in the 1910 Edinburgh Missionary Conference but slowly abandoned by mainline missiology in the first half of the 20th century. Furthermore, McGavran’s “fierce pragmatism”[5] and missionary experience led him to study and facilitate “people movements.” The urgency of evangelism also led him to develop “harvest theology,” which argued for the deployment of resources where the missionary iron is hot for a maximum gain.[6]

The institution’s immediate target group was career missionaries in their home service (or on missionary sabbatical). The main purpose of McGavran’s Church Growth Institute in Oregon, later incorporated into SWM, was for “experienced missionaries… [to] study the growth and non-growth of the churches in which they worked.”[7] The primary clientele were western missionaries, and the space of this church growth enterprise was the “mission field,” presumably in the non-western world. It was C. Peter Wagner who brought church growth study “home” to North America in later years.

The 1980s saw a drastic change in the life of SWM, when the balance of global Christianity tipped towards the south from 1981 onward.[8] The demographic changes in global Christianity in that period and the following decades have been staggering. The growth of African Christianity, with the growth of non-missionary churches, often called African Independent (or Initiated) Churches, is particularly noteworthy. Chinese Christianity returned with a strong sign of presence and strength, to a much surprised world mission watcher. Pentecostal-type churches have proliferated and provided growth energy globally.

Following this growth, the composition of SWM’s student body shifted from mid-career western missionaries to national church and mission leaders from various parts of the world. The focus of the school moved from a single emphasis on church growth to diversified specialisms. It is hard to ascertain the extent to which SWM/SIS contributed to the global growth of Christianity during these decades, but one thing is clear: the school was diligent in gathering data from various parts of the world, analyzing it, and drawing patterns and lessons to be applied elsewhere. The study of church growth-the main bread and butter of the school-continued to find new areas (such as the spiritual dimension) through the watchful eye of Peter Wagner.

These developments demonstrate that SWM/SIS was and is not afraid of new approaches if they prove to contribute to the expansion of God’s kingdom. But what role does SIS have in the new era of Christian mission, if we are going to see a radically new era of world Christianity and its mission? Two areas will be briefly examined.

Re-visioning Mission and Its Agenda Setting

What is required in the thinking and practice of mission is a global collaboration and joint efforts among mission thinkers, practitioners, and leaders. It will take experience, input, and reflections from both the growing South and the waning North. The North is still a vital partner, with its long history of mission engagement, and human, knowledge, and financial resources. Only the North can provide a self-analysis and discernment of the “received” mission thinking and practices.

SIS has proven its ability to call for or convene a global space of exchange, learning, and dialogue, capable of facilitating a global process in reshaping global Christianity and its mission. Regional theological institutions and mission networks can be part of the process. This convening power exists partly because American evangelicalism is relatively free from colonial baggage. Also, churches in the South resonate with SIS’s commitment to evangelism, which is why a good number of Christian leaders and mission practitioners are attracted to Fuller’s program. At the same time, the school has demonstrated its openness to experiment with new subjects and approaches that are useful for mission.

SIS has proven its ability to call for or convene a global space of exchange, learning, and dialogue, capable of facilitating a global process in reshaping global Christianity and its mission. Regional theological institutions and mission networks can be part of the process. This convening power exists partly because American evangelicalism is relatively free from colonial baggage. Also, churches in the South resonate with SIS’s commitment to evangelism, which is why a good number of Christian leaders and mission practitioners are attracted to Fuller’s program. At the same time, the school has demonstrated its openness to experiment with new subjects and approaches that are useful for mission.

With these unusual gifts, SIS can intentionally draw global stakeholders in mission, including major regional institutions, and begin to chart tomorrow’s Christian mission. But it will have to be far more than a discussion of methodologies; it will need to begin with the very foundation of mission.

In order for SIS to take up this historic and challenging leadership call, it will have to overcome several important obstacles. Among others, it will have to learn to think and see what the Holy Spirit is doing from a global perspective. Leaving an American evangelical perspective is hard, particularly with its own institutional stakeholders, whom the seminary is initially called to serve. It may take much convincing. The school needs to seek genuine global voices, such as an African voice: not an American missionary who once worked in Africa, but an African insider. It is equally necessary for the school to act ecumenically, rightly representing its student body while holding firmly to evangelical conviction.

Creation of Mission Knowledge

From the beginning, SWM/SIS insisted on the creation of knowledge, as shown in its top-ranked position in every 10-year survey on the production of dissertations on mission.[9] It broke new ground by bringing social science-anthropology in this case-to mission studies. In addition, its insistence on training mission practitioners through its programs resulted in the creation of knowledge-based practices. However, the training of mission practitioners is both an enduring commitment and a challenge to sustain. This emerges from a lingering dichotomy between professional degrees such as Doctor of Missiology and the academic one—namely, the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in North American higher education.

The quandary, then, is how SIS can remain a thought leader, especially in the reshaping of mission thinking and practice, while maintaining the training of mission practitioners as a priority. The creation of new knowledge will definitely require a continuing strength in the PhD program. Is there a way to bring practices (thus, practitioners) to the PhD regime? My answer is a definite yes, and two places may provide a helpful possibility. One is other disciplines, especially social science. Field data is often the most critical research base, and mission studies cannot be an exception. In fact, the list of SIS PhD dissertations, I believe, already proves this. The other is several successful models of PhD delivery in mission studies, such as the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, perhaps the largest PhD provider in Europe in mission studies, which has crafted its PhD delivery system mostly based on field experiences and data.[10]

This comes with several challenges. The first challenge SIS will have to face is the typical US PhD structure. If its program is realigned to make it more conducive to mid-career mature leaders with rich experiences of mission engagement, then it will have to make a part-time study readily available. The second, however, is more challenging: full-time resident course work, the most challenging requirement for many would-be candidates. Although building a general and broad knowledge base is essential for the candidates, since many of them come with rich experience both in practice and reflection, perhaps this can be negotiated with the accrediting body. There are strong arguments that, due to their being practitioners, each comes with varying levels of preparedness and deficiencies. This segment, then, can be customized to meet the unique needs of each candidate. (My study at the School of Theology was a brilliant example.) The third, perhaps most challenging, is the ability to go beyond SIS’s own faculty in order to radically expand its supervisory capacity. Again, this has been successfully done elsewhere. This way, SIS can continue its programs in professional doctorates as well as master-level training, especially to serve its immediate constituencies.

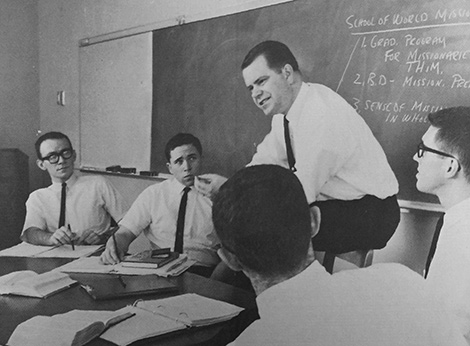

Photo of the first class of SWM in 1966.

Photo from a Fuller bulletin annoucing SWM in 1965.

(c) 2016 by Charles Van Engen. To be included in a forthcoming volume of essays edited by Charles Van Engen and tentatively titled Mission with Innovation, to be published by InterVarsity Press in 2016.

[1] Todd M. Johnson and Sun Young Chung, “Christianity’s Centre of Gravity, AD 33-2100,” in AOGC, pp. 50-51.

[2] Patrick Johnstone gives us a stunning visual presentation of continental changes of Christian demography between 1900 and 2015. The contrast between the growing continents and declining ones is striking. Patrick Johnstone, The Future of the Global Church: History, Trends and Possibilities (Colorado Springs: Global Mapping International, 2011), 95. This general trend in the middle of the twentieth century has been statistically supported in various studies.

[3] SWM/SIS, p. 64, quoting an insightful reflection of Wilbert Shenk on the missional context of the 1960s.

[4] SWM/SIS, p. 78.

[5] SWM/SIS, p. 70.

[6] SWM/SIS, p. 78.

[7] SWM/SIS, p. 13.

[8] Johnson and Chung, “Christianity’s Centre of Gravity, AD 33-2100,” pp. 50-51.

[9] Robert J. Priest and Robert DeGeorge, “Doctoral Dissertations on Mission: Ten-Year Update, 2002-2011 (Revised),” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 37:4 (Oct 2013), pp. 195-202.

[10] D.P. Davies, “The Research Contribution of OCMS,” Transformation 28:4 (Oct, 2011), pp. 279-85.

comments