A Time For Everything

I went to see Talgat mainly because that is what friends do in Central Asia—spend time together. He is not a ministry project, but a friend whose company I enjoy. Nevertheless, I also wanted to see him because I knew Talgat was struggling with problems in his ministry, and I thought that he might need someone to talk to. Little did I know that what he needed to say was exactly what I needed to hear.

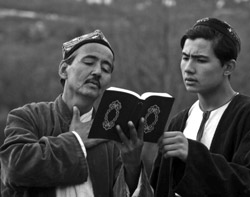

My friend Talgat is a typical Central Asian man—extremely loyal to his family, generally likeable, and not given to a lot of words. In other ways though, he is most extraordinary. For a start, he has been a follower of Isa for more than seven years. Few of his people fit that description. Not only that, but he has exercised authentic Christian leadership for most of that time. He doesn’t carry a title like “Pastor” or “Reverend,” but he is the sort of man Paul wrote about in his first letter to the young Timothy:

The overseer must be above reproach, the husband of but one wife, temperate, self-controlled, respectable, hospitable, able to teach, not given to drunkenness, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, not a lover of money. He must manage his own family well and see that his children obey him with proper respect.

In Talgat’s world, these qualities speak far louder than the seminary degree others aspire to. Maybe that is the way it should be.

As with every other significant conversation I’ve had in Central Asia, this one began and ended over a cup of tea, with a meal somewhere in between. Nothing is done or said in a hurry. All those who would take a pilgrimage into this land of Bactrian camels and Oriental carpets should remember that the nasty American habit of quickly getting down to business feels very rude in this part of the world.

Talgat and I sat in the living room where we ate and talked alone. For the most part, his wife Dilbahar kept to the kitchen. It was not for lack of something relevant to say, for at key moments she would briefly join us and share what was on her mind. But mixed company at a meal does not sit well with my friend, so one stern look was usually enough to return her to the kitchen.

Please don’t judge him too harshly in this. Remember, we are the foreigners in his house. This is also a good reminder that Central Asia is an altogether different place from the West.

After the meal I tried to draw Talgat out, but to do so I would have to carefully watch my natural tendency toward directness. If I wanted to know what was going on inside this man, I would have to be discreet and indirect—an art I have yet to master.

I decided to begin by asking his thoughts on a couple of general ministry questions. I was certainly interested in the ideas of one who could rightly be called “a pillar of the church” in Central Asia. But more than that, I hoped my questions might start him talking about the more troubling things on his mind.

Talgat gave me a vague answer to the effect that they had “made good progress” over the past five or six years. There was still “much to do,” but the groundwork had been done. Then, from out of nowhere, he asked me an odd, leading question: “How do you understand your work here? How do you define your role as a missionary?”

Talgat gave me a vague answer to the effect that they had “made good progress” over the past five or six years. There was still “much to do,” but the groundwork had been done. Then, from out of nowhere, he asked me an odd, leading question: “How do you understand your work here? How do you define your role as a missionary?”

Remember, this question was coming from a man who had been a follower of Isa longer than I had lived in Central Asia. He had probably known as many missionaries as I have. Something important was lurking under the surface of his query.

Talgat must have noticed a puzzled look on my face, so he tried to clarify by saying that he had “never really understood Westerners,” and wanted a clearer picture of how we think.

Since I had been trying to develop the art of being indirect, I decided not to give him a straight answer. I simply asked him to read some words from one of my favorite missionary thinkers:

By the grace God has given me, I laid a foundation as an expert builder, and someone else is building on it. Each one should be careful how he builds.

After reading this passage, Talgat spent a few minutes in thought. Then he replied, “I think I’m getting a revelation of something here.”

Looking back on the moment, I believe he had already given a great deal of thought to what he was about to say. He had meditated, if not specifically on this verse, certainly on the subject in general. Nevertheless, what followed was certainly a revelation for one person in the room.

“Paul was an apostle,” said Talgat slowly, “which means he was a ‘sent one.’ He went around starting churches. So what he describes here is the way apostles, or ‘sent ones,’ are supposed to start churches. I’ve never seen this before, but it makes sense because Paul was explaining something that is normal in our culture.”

I had to think quick. I had looked at the back pages of a Bible a lot during my Sunday School days, but I never saw a Journeys of Saint Paul map that included Central Asia. So how is it that Paul intersected with Central Asian culture? Talgat certainly had my attention.

“In traditional culture,” he continued, “when someone wants to build a house, they invite all their friends and family to come help. On the appointed day, everyone comes ready to work—and work hard. They all know that with enough men, and one hard day’s work, the foundation of a new house can be laid. So that is the focus. They do not worry about doing other things, the foundation is what they came to build. While the men are working, the women prepare a huge, traditional meal. But even though there is much to be done, it is much more than work. It’s a celebration. A new house is going up.”

As Talgat talked, I could picture the preparations I’ve watched many times for other big events like weddings or funerals. The men would be occupied with whatever needed to be done outside, while the women washed and cooked the rice, cut piles of carrots, and prepared the meat. It is the same at all big parties.

He continued painting his picture for me. “By late afternoon, the foundation is finished. Some of the men start cleaning up, while others quickly assemble a sort of long table for the feast. Soon there will be lots of eating, laughing, and drinking tea.” As he was speaking I could see the men in my mind’s eye, sweaty and bone-tired, but glowing with a sense of accomplishment from the day’s labors.

“Later that night, when the eating, music, and dancing are over,” continued Talgat, “the owner of the house stands up to profusely thank all who answered his call for help. He freely admits that he could never have done it without them, and ends by telling them that he is forever in their debt. They were there the day the foundation was laid.”

Then in an unexpected anticlimax, Talgat finished his story. “And then everyone goes home.”

I sat there startled; it seemed too abrupt. There had to be more to it, but when I pressed him on this point, Talgat’s rationale went something like this: “The people came to do one thing-to lay the foundation. They did what could not have been done without their help. When that is finished, it is the owner’s business to finish his own house.” As much as I wanted something more, I could see the logic.

But this was not all. My friend was on a roll and he continued to expound his thoughts. “And just like Paul, you foreign missionaries are the helpers in our tradition. God called you from all over the world to come to Central Asia and help us lay the foundation. We never could have done it without you. But now that part is soon to be finished. It is almost time for us to prepare a great feast and tell you how much we appreciate all your hard work and sacrifice for our people.”

My thoughts drifted back to the Apostle Paul’s words, trying hard to apply them to Talgat’s story and to the missionary practice I have seen in Central Asia. Then it dawned on me why Paul the church-planter did not stick around to finish the house. Why? Because it is the owner’s job to do so.

Who better to decide where to put windows, or how many bedrooms are needed? Is it not the one who will live in it? Paul tells us that there is only one foundation that can be laid—Christ Jesus. But could many floor plans be built on this one foundation?

My mind was pulled back to the present by Talgat’s voice. “And then you will all leave.”

His directness caught me off-guard and I was silent for a moment.

“Is that how it works?” he pressed. “Will all the missionaries leave soon so we can build the church to look like we want?”

What could I say? How could I tell him that there is a right and proper way for some pilgrims to stay on past the foundation stage? Would he even consider that our partnership could be helpful long into the future? How might I explain the ideal scenario in which we foreigners move to the background while the “owners of the house” take the lead?

Indeed, how could I enlighten my friend to such idealistic church-planting theory when his experience had painted a much different picture? Missionaries fading into the background is a model he has seldom seen. Most missionaries can talk at length about such ideas as theory. Yet few church-planters are ready, in practice, to act like the Apostle Paul, truly risking the leadership of a new church into the hands of local believers.

However, I didn’t need to tell my friend all this. He already knew. He had known for years. In fact, as I pondered on this issue, I realized that watching foreigners lord it over the local church has probably been the bitter root feeding most of Talgat’s thorny ministry problems over the years. Could it be that this story was his polite, Central Asian way of telling me so?

For some strange reason, we foreign missionaries seem to forget that we are the pilgrims, the temporary ones. This land through which we sojourn, no matter how much we come to love it, is not our home. Our new brothers and sisters are the ones destined to live in the house. They, and their children after them, will have to deal with what we do, both good and bad. And because of our convenient memory lapses, we somehow believe that it is our right to perpetually stay on and supervise.

We would probably still be welcomed as helpers, but not as overlords. And that is precisely where the problem arises. Many missionaries have the hardest time moving out of the limelight and off to stage left. It’s as if we don’t really believe that God will work through our local brothers and sisters with the same power that He works though us. Could it be that sometimes our faith is in ourselves rather than in the Spirit of God?

Talgat was right. When the foundation is laid, this house, the indigenous church in Central Asia, should be finished by the ones who will live in it. Whatever continuing roles we foreigners may rightly fill, it is fundamentally different from that of local leadership. They must be the ones, led by the Holy Spirit, who frame the windows and decide what color to paint the walls. In fact, that is the only way the church will ever truly be indigenous.1

comments