Water and Poverty

One Organization's Approach: A Conversation with Tearfund's Frank Greaves

Tearfund is an organization that was born in the 1960s out of The Evangelical Alliance in the UK. It is recognized for its professional expertise in development, disaster response, and advocacy, and follows the biblical mandate that helping communities in need is central to the purpose of local churches, wherever they are. Water and sanitation are major areas of focus for Tearfund as it works with local church partners and disaster response teams in more than 40 countries around the globe.

Mission Frontiers: At Tearfund, you talk quite a bit about the interconnectedness of material and spiritual need. Tell us about that.

Frank Greaves: Tearfund is grounded in the principle of integral mission (from the Latino term “misión integral”). To us, this embodies the full gospel, representing both the voice and the hands of Jesus. We do not separate demonstration and proclamation, believing that we are here to serve, love, and have compassion—to walk with the poor, identify with them, and to know them by name.

Frank Greaves: Tearfund is grounded in the principle of integral mission (from the Latino term “misión integral”). To us, this embodies the full gospel, representing both the voice and the hands of Jesus. We do not separate demonstration and proclamation, believing that we are here to serve, love, and have compassion—to walk with the poor, identify with them, and to know them by name.

Before I came on staff here in London, my wife and I were on the field for ten years, working with the skills and knowledge that we had; my wife Laura is a nurse, and I am a water engineer. On a daily basis we were able to talk and engage with those that we served—local staff and partners, community members and pastors—talking about the work we were doing, our faith, and what motivated us to be there. To me, the one-to-one relationships we were able to build during those years exemplify what I am talking about. It’s about sharing—because, of course, we learn and are ourselves transformed as we take part in integral mission.

At Tearfund, I’d say that we ultimately view poverty as broken relationships—with God, with ourselves, one another, and with our environment.

MF: One of the areas where Tearfund focuses, and the area of your own expertise, is Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH). How does WASH fit into your work among the poor?

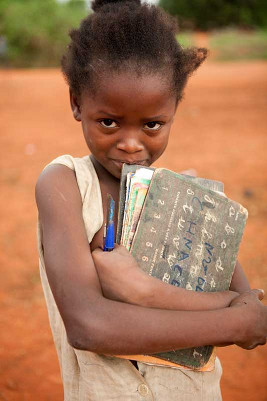

FG: WASH is so fundamental. It’s the aspect of development that has the most direct causal influence on all the rest: health, education, economic poverty, food security, gender equality, environmental sustainability, the list goes on. On a personal level, every time I visit partner churches and communities to assess WASH projects, I am struck by the way water and sanitation affect peoples’ dignity —particularly women, children, and the elderly.

MF: Has Tearfund had different models or approaches to water development or WASH in its history? What did they look like, what did you learn from them, and how has the journey shaped your current approaches?

FG: Tearfund began working with water development very early on, as early as the late 60s. We allocated resources to digging wells, drilling boreholes and the like. In those days we had a bit of a top-down approach, where the emphasis was on what we were doing in the community. We now focus on the self-empowerment of communities, building their capacity to develop sustainable and replicable (there’s a term we don’t hear enough) solutions to their own problems. In the early years we thought in terms of “WatSan”—Water and Sanitation—with a focus on the technical side of things that mostly involved engineers building systems. Usually these were combined with health and hygiene projects, but these days we see that the full impact of water, sanitation, and hygiene can only be realized in an integrated approach. Hence… “WASH.” Incidentally, the “A” in WASH is also important to us—we use it to refer to Advocacy, which is an important component of all this. Governments are the ultimate service providers, and we should work with governments at both the local and national levels to build their capacity.

In addition to the integration of the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene components of WASH, another central focus is on a demand-led livelihoods approach to this and other areas of development, as opposed to a supply-driven approach. This means that the demand and stimulus of any particular project come from analysis and decision-making by future beneficiaries in communities themselves. It starts with enabling the community to perceive and prioritize its own needs, and to understand its roles and responsibilities in addressing their own needs. This approach can include use of tools like Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), Participatory Hygiene and Sanitation Transformation (PHAST), and Water Safety Plans—a particular favorite of mine.

In addition to the integration of the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene components of WASH, another central focus is on a demand-led livelihoods approach to this and other areas of development, as opposed to a supply-driven approach. This means that the demand and stimulus of any particular project come from analysis and decision-making by future beneficiaries in communities themselves. It starts with enabling the community to perceive and prioritize its own needs, and to understand its roles and responsibilities in addressing their own needs. This approach can include use of tools like Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), Participatory Hygiene and Sanitation Transformation (PHAST), and Water Safety Plans—a particular favorite of mine.

Social marketing is another demand-led livelihoods approach. So, for example, instead of supplying latrine materials for, 500 households, we would prefer to work through an empowerment process to stimulate demand for household latrines, and to work in parallel with local artisans and vendors to build or sell latrine materials that local people can afford. A latrine that is basic, but regularly used and well maintained, does the job.

MF: What does it take for a community or church to recognize that the development process is theirs, and not owned by a government or agency?

FG: Well, there are the tools themselves… when the process is demand-led, people naturally come to see the causal link—expressing the notion that “we did this,” “this is our journey.” A key underlying issue with these tools is good facilitation by the implementing agency, with regular close follow-up. We’ve been focusing on church-community mobilization processes that enable the local church to play the key role of facilitator—helping its own community identify not only its collective needs and aspirations, but how the community itself can begin to address those needs.

MF: How can agencies and churches in the global North participate in integral mission-based WASH programming without creating dependency?

FG: Raising awareness of good development practices and methods is important. I get quite a number of inquiries each week from well-intentioned individuals and churches who want to “provide water” for a particular community, orphanage, or school in less developed countries.. Their heart is in the right place, but their view is generally top-down. It’s quite rewarding to help them understand the real scope of what the community needs—what it takes to set up local water management, sustainable local supply chains, and integrate it with the broader issues of hygiene behaviors and sanitation services. It’s not just a matter of drilling the well or installing the right pump. How can we use the money we’re investing to bring sustainability, to stimulate people to really own and feel accountable to their project?

At some point in the future, the local church will be there, but we may not even have access to any particular country in the future. We can’t expect communities and churches to sit around waiting for external funding. The “aha” moment that I often hear over the phone as enquirers come to understand these issues reflects this core belief that we’ve had as a sector over the years.

MF: Talk to us about how local churches get involved with WASH in their own communities.

MF: Talk to us about how local churches get involved with WASH in their own communities.

FG: Well, in 2007, when we were at the midpoint of the fifteen-year Millennium Development Goal (MDG) period, a colleague and I began to do some research on this very issue. We wanted to understand the impact of churches we had supported during the first half of the MDGs (2000-2007), to predict how our support of local churches would impact the second half of the MDG period (2008-2015).

We didn’t set out to develop a model for church engagement in hygiene and sanitation, but that’s what ended up happening. As we looked at data and stories of impact, a pattern emerged—a set of impactful roles that churches characteristically play in their communities: 1) messenger, 2) demonstrator, 3) implementer, 4) advocate, and 5) guardian of the benefits of WASH. We explored the pattern and elaborated on it because we wanted to see how these roles were adopted and developed by churches. We wrote about the pattern, with case studies illustrating it, in a document called “Keeping Communities Clean,” which you can read online.

This report, and our experience as a whole, counteracts the notion that WASH is technical, and that there is no real place for the Church in this sector. The Church has an amazing role—a foundational role in WASH.

It’s also important to note that we work beyond the bounds of traditional churches, bringing our Christian principles and witness into dialogue with communities of other faiths. We’ve had great success working with Islamic mullahs and their flocks in some otherwise hostile areas, as we seek transformation amongst the communities we support. We’re able to build bridges of trust as they see our integrity and ability to follow through, rather than just talk—they’ve heard quite enough empty words. It’s also interesting to note that discussing good hygiene and sanitation practices, something that both our Old Testament and the Qur’an speak about, is an easy way to open the conversation. Ultimately, the fact that we—and more importantly, our local partners—are people of faith reaching out to the poor in these communities—sharing meals together, talking about our experiences, and loving with no ulterior motive—all this speaks volumes.

MF: Which of the roles outlined in “Keeping Communities Clean” have been the most effective, in your experience to date? Can you tell a couple stories of particular communities or churches to illustrate?

FG: All of the roles can be transformative, but I think the first, most fundamental role of “messenger” can be so effective and straightforward—and is clearly biblical. This is a role that depends on good facilitation and natural leaders, which can sit very naturally with the Church.

The role of messenger is generally combined with that of “demonstrator,” obviously, because whether we’re talking about the gospel or just good hygiene and sanitation practices, these should go together. The combination of just these two can be very simple but extremely powerful.

There’s also the role of “advocate”—speaking out on behalf of the poor, which is clearly a biblical idea as well. A great example of this is the work of Tearfund’s local partner in Brazil, FALE. In 2006, FALE began a campaign that mobilized local churches to prayer, and advocate with Brazil’s national government to establish policies that would bring safe sanitation to even the poorest Brazilians. In 2008, the Government of Brazil adopted a pro-poor national sanitation policy—largely due to FALE’s efforts

There’s also the role of “advocate”—speaking out on behalf of the poor, which is clearly a biblical idea as well. A great example of this is the work of Tearfund’s local partner in Brazil, FALE. In 2006, FALE began a campaign that mobilized local churches to prayer, and advocate with Brazil’s national government to establish policies that would bring safe sanitation to even the poorest Brazilians. In 2008, the Government of Brazil adopted a pro-poor national sanitation policy—largely due to FALE’s efforts

to mobilize the Brazilian Church.

Kigezi Diocese in southwest Uganda is a fantastic example of Church leadership in WASH. This network of churches plays several of the other roles as well, such as “implementer,” but the one that stands out to me is their work as a “guardian” in maintaining WASH services for the long term. The last time I visited Kigezi Diocese, was about three years ago. I went to see some of the area’s spring protection areas and gravity water systems, and the way that they were kept up and utilized, and the functionality and transparency that characterize them. One would easily be mistaken to think that they were constructed two months ago, but they were in fact completed 16 years ago. The household subscription service that was originally started to gather funds for maintaining systems has often been loaned to beneficiaries of the spring project, for example, to purchase seeds. And so the program is gaining benefits not only attributable

to greater access of safe water, but also to the livelihoods of individual families. The need to follow up their programs is well understood by Kigezi Diocese. Much

of the follow-up is done by volunteer women from within those churches who visit villages every month to be sure services are working and continue to have an impact in each community.

MF: What do you think is possible in the next 10 years in terms of the global Church and WASH? What would need to happen for that vision to take place?

FG: Well, Tearfund’s official 10-year vision is to see 50 million people released from material and spiritual poverty through a network of 100,000 local churches. My own personal vision as I think about it today—not speaking for Tearfund here—is that governments and agencies would increasingly look to the Church as a natural partner in serving the poor through access to water, sanitation, and hygiene. And I mean a true partner, not just a convenient grassroots organization or a conduit for their own projects. This would have all sorts of implications for finance, management, governance, and all of the background support WASH services need.

FG: Well, Tearfund’s official 10-year vision is to see 50 million people released from material and spiritual poverty through a network of 100,000 local churches. My own personal vision as I think about it today—not speaking for Tearfund here—is that governments and agencies would increasingly look to the Church as a natural partner in serving the poor through access to water, sanitation, and hygiene. And I mean a true partner, not just a convenient grassroots organization or a conduit for their own projects. This would have all sorts of implications for finance, management, governance, and all of the background support WASH services need.

We once had a visitor at a staff conference at Tearfund who stood on the podium and said, “I believe that the days of the conventional ‘northern’ development agency are numbered,” and I think he may be right. With communications and direct support being what they are today, I think it is really becoming possible to move the power, decision-making, and resources into traditionally poor churches and communities, and local organizations, for them to truly lead the process themselves.

comments