The Future of Ethnodoxology in Arts and Mission

Ethno-WHAT? In the early 1990s, the term ethnodoxology did not exist. Coined by Dave Hall, its first appearance in print was in September 1997.1 As we launched the organization that became the Global Ethnodoxology Network (GEN), many people asked us, “Why would you want to use a word no one understands to describe what you do?” Our answer? We needed an innovative word for this discipline emerging from the intersection of missiology, ethnomusicology, worship studies, Scripture engagement, linguistics, and other disciplines.

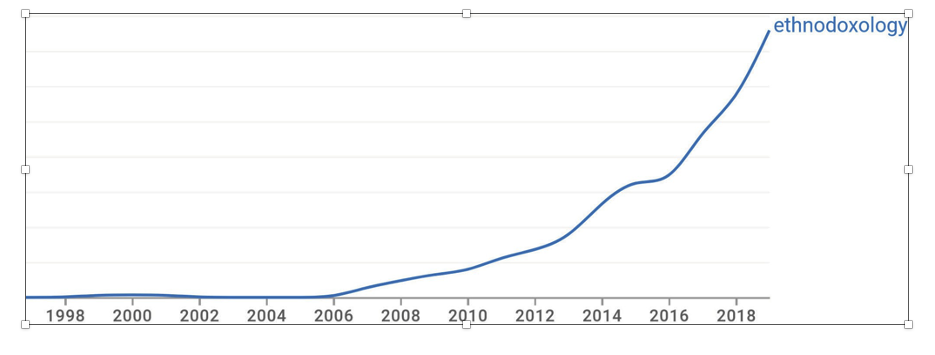

The growth of the term’s use in the last 20 years has vindicated that choice. In the last year, for example, 2.5 percent of the people who found the GEN website (worldofworship.org) did it by googling the term ethnodoxology. And there were 1,367 views for the “What is Ethnodoxology” page (out of 11,835 total views for the site).2 The chart below from the N-gram site shows the growth of the term in publications archived by Google books through 2019.3 It is clear from the trajectory that, although it took almost a decade for the term to make its way into print, the second decade demonstrated exponential growth. In addition to an upsurge in the use of the term, the ethnodoxology approach has spread during that time as mission agencies, non-profits, and training institutions begin to incorporate ethnodoxology values into their thinking, methods, and curricula.

Given the rise of ethnodoxology values and methods and its expansion into the beginnings of a global movement, we wanted to explore this question: What might be the future of ethnodoxology as it intersects with arts and mission? Interviews with some global leaders in the GEN network revealed vibrant hopes and dreams for the next decade of ethnodoxology’s future. What follows is an exploration of some of their ideas.

Ethnodoxology and Social Innovation in Restricted Countries

Grace4 returned to her country in East Asia after receiving graduate level training in an ethnodoxology-related degree. She told me, “When I returned to my country, I was hit by a new reality. As the restriction of religious freedom tightened, many well-trained expats who were active in the frontiers were gone, and their work came to a halt. As a result, it left big holes in our field work. The intensifying persecution, however, was showing us that the traditional approach was not working. Instead, innovation was urgently needed. In the face of these new challenges, I felt a push from the Lord to explore a sustainable approach to mission.”

As Grace responded in obedience, the Lord opened an opportunity to work with a non-believing social enterprise centered on bringing ecological, economic, and cultural sustainability to marginalized mountain communities in the region. The people of this region excelled in producing beautiful and complex arts but had little chance to leverage them for financial sustainability. Her colleagues’ business is an example of social innovation (fostering the wellbeing of the community through social enterprise).5

Grace’s colleagues renovated some traditionally built architectural spaces that had become dilapidated, converting them into a school that soon began to attract students from all over the country and even beyond. Grace developed the curriculum for educational packages, allowing these students to study endangered but beautiful forms of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) such as local embroidery styles. She arranged for local artisans to give lessons and teach skills, while incoming students learned how to do research into local art forms. In addition, the students coming also commissioned new works from the artisans.

Grace says, “Inspired by my working experience with the social enterprise, I felt an urge to mobilize the church to get out of the Christian bubble and connect to the society through integral mission. Meanwhile, I started to dream of creating an Arts and Culture Incubator for ethnodoxologists to leverage their training in arts and culture research, while connecting the needs of society to the market and providing economic thriving for communities. Along the way, believers can build deep relationships with people in communities where normally they would not be welcome. Grace hopes that this “Arts and Culture Incubator” model will provide inspiration for other fields to use a social innovation model, especially in restricted areas.

Ethnodoxology and Digitality

John Paul Arceno6 notes the future of ethnodoxology will be increasingly digital. He observes worship increasingly happening in hybrid and digital spaces. Furthermore, he believes digitality will affect more and more of our work in missions: “Digital communities can be real, embodied cultural people groups. We need to adapt our ministries to indigenously engage with these cultural groups in their own language [of digitality].”

Ethnodoxology Resources and Training in More Languages

Juan Arvelo Montero, a GEN board member from Venezuela serving with WEC’s Arts Release ministry in Spain, told me this: “When I discovered ethnodoxology, it was like a new world for me. I thought, why didn’t I learn about this before? My vision is to train Spanish-speaking ethnodoxologists. In 10 years, I would love to see a program established to train ethnodoxologists in Spanish and other languages.” He noted that the field of ethnodoxology was mainly developed in English, but now it needs further development in other languages. Juan is dreaming of more than just one program. He said, “I could see this starting at Dallas International University, but it needs to spread to other institutions as well. Initially, we need to provide education at the graduate diploma level, but in the long term we need a doctorate for Spanish speakers to study ethnodoxology.”

Drawing on Michelle Petersen’s article7 applying language development principles to the arts, Juan notes all three levels of development she outlines for arts are needed for training initiatives as well: status development, corpus development, and acquisition development. He says, “We need to increase the status of ethnodoxology in the Spanish speaking world, we need to create more literature, and we need to train more people.”

Juan is already working to partner with Spanish-speaking ethnodoxology colleagues Josh Davis (Proskuneo) and Jhonny A. Nieto Ossa (ALDEA) to plan a Spanish-language online course. Jhonny, a GEN leader from Colombia, also shares Juan’s vision, adding that the future of ethnodoxology will see a growth in workshop facilitators who can function in multiple languages.

Jhonny also dreams of the development of ethnodoxology applications for those with special needs. Other applications of ethnodoxology, such as multicultural worship and multigenerational worship are also growing and promise to play a more prominent role in the future of the field.

Retired professor and GEN Certification Committee member John Pfautz adds this vision for ethnodoxology education: “I envision a course that travels well to various regions of the world that will train teachers in educational centers, churches, and under the baobab tree. This course, adapted for each local situation, should teach appreciation for local arts and music, affirm local efforts, and provide encouragement as well as tools for support of local artists and musicians.”

Ethnodoxology & Polycentric Mission

Elsen Portugal, GEN board member from Brazil with the first PhD in Ethnodoxology wrote, “I believe one of the directions towards which the discipline is going is polycentric mission (from everyone to everywhere). Although we do not wish to deny or forget that mission was practiced typically from ‘us’ to ‘them’ for centuries, I believe that, through the interconnectivity of this world, ethnodoxology can truly support the global Church, mutually serving one another and building of the Body of Christ—to everyone from everywhere.” The board of trustees for the Global Ethnodoxology Network (GEN) already represents this reality (see https://worldofworship.org/about/board/), and even the contributors to this issue illustrate the global engagement of its members in ethnodoxology practice.

The implications of polycentrism extend beyond board composition and contributors to publications, however. John Pfautz expressed my own thoughts well when he wrote his dream for the future: “There has been enough buy-in globally that regional leadership in GEN will be mentoring a flourishing group of folks who not only engage via technology, but meeting face to face to share dreams, successes, and challenges unique to specific people in that specific part of the world. Administration, leadership, centers of education, will likely be experienced regionally.” The GEN Board shares this vision and is investing in those leaders already (our “GEN Global Advisory Council”). Their voices are increasingly shaping the future of ethnodoxology.

You can meet them at this GEN YouTube playlist, titled “I am an ethnodoxologist.”8

Héber Negrão (Brazil), PhD student in World Arts at DIU and GEN board member, integrates many of these ideas above into his vision for the future: “I foresee ethnodoxology becoming a required course in every center for missionary training in the next years. Ethnodoxology is essential to understand cultural ways of worship from different people groups. In the historical moment we live in today, missions are accomplished from everywhere to everywhere, and that scenario is here to stay. The imprint of Western Christianity will gradually abate, however ethnocentrism will continue as a marker of our fallen humanity. As missionaries from the Majority world take the Gospel to other countries, they will need to know how their intended audience uses their arts to respond to God. And they must resist the urge to use their own artistic expressions and cultural assumptions in their missionary efforts. Given the ruthless effects of globalization and the beautiful diversity God has created in all cultures, I am convinced that ethnodoxology is truly indispensable for the future of multicultural Christianity.”

Where are we headed?

If there is anything the 2020s are teaching us, it is that global trends can be difficult to predict. But the future of ethnodoxology may well include the hopes of these GEN leaders, as we grow into 1) creative models of social innovation and holistic ethnodoxology ministry, 2) embracing digitality while not abandoning our commitment to regional in-person gatherings, and 3) polycentric leadership and teaching staff who provide ethnodoxology learning opportunities in a broad variety of languages in regional centers around the globe.

In the final chapters of the Bible, we see the certain hope of a new heaven and a new earth, in which the New Jerusalem is flooded with the light of the glory of God. Revelation 21 describes the splendor, glory, and honor of the nations (that includes their artistic treasures!) that will be brought as tribute to the Lamb (Rev. 21: 24, 26). With that end picture in mind, we hope you will join us in working toward a future in which communities of Jesus followers in every culture engage with God and the world through their own artistic expressions, offering them to the Lord in the worship He is due.

comments