Four Ways Culture & Worship Relate

Christianity, like every other religion, was born in a particular historical and cultural context, in a particular time and place.1 For Christianity, this context happened to be the ancient Middle East at the beginning of the first century. While the historical context of Christianity’s birth is unchangeable and static, like the recorded time and place on one’s birth certificate, its cultural context no longer exists. Culture by definition is dynamic and constantly changing, sometimes slowly and gradually, at other times rapidly and dramatically.

Moreover, while every religion, including Christianity, has its solid, unshakable foundation, the form of a religion is flexible, based on the cultural mold in which it finds itself. From this paradoxical situation, a tension is born between preserving the orthodoxy of one’s religion and trying to adapt to one’s context with intelligence and versatility in order to stay relevant to contemporary cultures.

Christianity has always stood in tension with prevailing cultures, no matter where it existed. But as humans we hate tension. We are wired to resolve tension. We look for symmetry. We want a clean end to every mystery novel, an answer to every complex riddle. But what happens when Christianity insists on maintaining its foundations and its original cultural forms, no matter what new culture it finds itself in? What happens when Christians see the tension as a chaotic mess, rejecting its constant demands to review one’s priorities and revisit difficult questions? A crisis occurs.

Christianity has always stood in tension with prevailing cultures, no matter where it existed. But as humans we hate tension. We are wired to resolve tension. We look for symmetry. We want a clean end to every mystery novel, an answer to every complex riddle. But what happens when Christianity insists on maintaining its foundations and its original cultural forms, no matter what new culture it finds itself in? What happens when Christians see the tension as a chaotic mess, rejecting its constant demands to review one’s priorities and revisit difficult questions? A crisis occurs.

A survey of various Christian traditions shows us that some churches try to resolve the tension by downplaying the differences between culture and faith. They try to blend in by matching their beliefs and practices—their entire religion, form and foundation—to those of the contemporary culture. History has proven over and over again that such faith communities lose their salty effectiveness (1 Sam 8; Matt 5) and give up their call to help reshape and reform culture (John 17). What was originally a healthy tension breaks down into bland duplication of the ungodly values of the context—a crisis.

Other Christian traditions have tried to resolve the tension by taking the opposite extreme, isolating themselves in opposition to the culture. This can take the passive shape of retreating to fundamentalist convictions, insisting that faith must be practiced in its original and purest forms, crediting the “good ol’ days” for bygone exuberance and growth. But it can also become aggressive, imposing itself on others, fighting about differences in worldview, faith, and practices—a crisis.

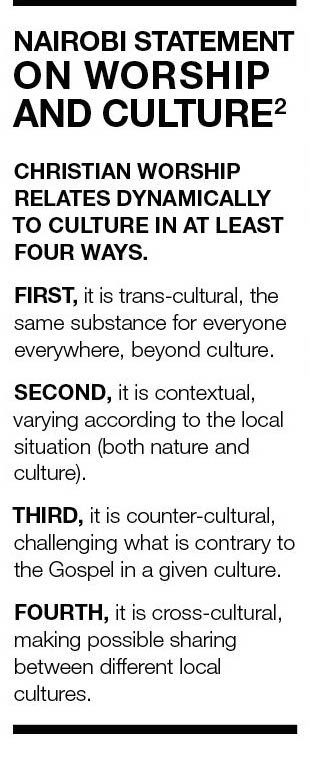

In their wisdom the writers of the Nairobi Statement foresaw the shadow of such crises hovering over the church in our human tendency and temptation to resolve tension at all cost. In an attempt to navigate away from these crisis points between Christianity and culture, they produced this document to help churches view the tension as an ongoing conversation to be protected, preserved, and even promoted. They have carefully designed a four-way conversation in which each persona has a role to perform, yet always remains in dialog with the other partners.

In their wisdom the writers of the Nairobi Statement foresaw the shadow of such crises hovering over the church in our human tendency and temptation to resolve tension at all cost. In an attempt to navigate away from these crisis points between Christianity and culture, they produced this document to help churches view the tension as an ongoing conversation to be protected, preserved, and even promoted. They have carefully designed a four-way conversation in which each persona has a role to perform, yet always remains in dialog with the other partners.

They have chosen to focus on worship as “the heart and pulse of the Christian church” (section 1.1), the most regular corporate event that is both expressive and formative of the beliefs and practices of a faith community.

FIRST: CHRISTIAN WORSHIP IS TRANSCULTURAL

Moreover, while every religion, including Christianity, has its solid, unshakable foundation, the form of a religion is flexible, based on the cultural mold in which it finds itself. From this paradoxical situation, a tension is born between preserving the orthodoxy of one’s religion and trying to adapt to one’s context with intelligence and versatility in order to stay relevant to contemporary cultures.

Christian worship contains the same substance for everyone everywhere. In all its diverse expressions, it is beyond culture. This is true not only of the central actions mandated by Scripture, but also of the centrality of the person and work of Jesus Christ (section 2.2).

This transcultural dimension is probably the single most important factor to the sensed unity of the worldwide church, visible and invisible, across time and space. We read the same letter to the Romans which was read long before us by Saint Augustine in Northern Africa and Luther in Western Europe. We remember and celebrate Christ’s death and resurrection in the Lord’s Supper, in parallel with believers in a megachurch in Korea, and in a reed-roofed hut in the Amazon. We all sing the Psalms, with our own musical styles, instrumental accompaniment, and languages.3 Understanding these universal and ecumenical elements of Christian unity gives local churches the freedom to use disciplined creativity for authentic contextualization.

SECOND: CHRISTIAN WORSHIP IS CONTEXTUAL

As we walked around his home island of Sulawesi, my Indonesian friend remarked, “You’ve never seen anything like this.” And he was right. I’d never seen architecture so unique and magnificent. The traditional homes of this particular people group are built on stilts of heavy logs, with open space under the house for animals and kitchen waste, an enclosed upper level where people live, and covering the whole structure is a saddle-shaped roof that rises at both ends like the fore and aft of a giant ship. The houses were covered with exquisitely carved wood panels painted in red, white, black, and yellow.

On Sunday we walked to church, and I don’t know why I was subconsciously expecting a brick building on street level with a paved parking lot, wooden pews covered with red velvet, and organ pipes up front with wood trims to match the pulpit, table, and font. And I don’t know why I felt shocked when instead my eyes were forced upward in the direction of the high stilts to a church building that looked like a larger version of everyone’s homes, with a set of stairs to climb up to the sanctuary (a fitting image, I thought). Why was I surprised by the intricate wood carvings and paint adorning the pulpit and table (their font was the ocean), and an open floor with a notable absence of any pews or seats?

Worship reflects local patterns of speech, dress, architecture, gestures, and other cultural characteristics. Jesus’ incarnation into a specific culture gives us both a model and a mandate. The gospel and the church were never intended to be exclusive to or confined to any one culture. Rather, the good news was to spread to the ends of the earth, rooting the church deeply into diverse local cultures. “Contextualization is a necessary task for the church’s mission in the world” (section 3.1).

Worship reflects local patterns of speech, dress, architecture, gestures, and other cultural characteristics. Jesus’ incarnation into a specific culture gives us both a model and a mandate. The gospel and the church were never intended to be exclusive to or confined to any one culture. Rather, the good news was to spread to the ends of the earth, rooting the church deeply into diverse local cultures. “Contextualization is a necessary task for the church’s mission in the world” (section 3.1).

In his book on global worship, Charles Farhadian stresses how important it is to “appreciate the immense variety of expressions of Christian worship in order to take seriously the social and cultural context that plays such a significant part in worship…[with] emphasis on culture as the potential, not the problem of worship.”4

The Nairobi Statement outlines two useful approaches to ensure adequate contextualization. First, dynamic equivalence—which involves re-expressing components of Christian worship with something from a local culture that has an equal meaning, value, and function. For example, the lordship of Jesus is taught among the Maasai tribe in Kenya by painting a black man dressed in a red robe, since red is the color of royalty and is always worn by the village chief. The second approach is creative assimilation, which involves enriching worship by adding pertinent components of local culture. For example, in Egypt the harmonic sound of an oud (lute) is used to add a fuller expression to psalms of lament.

Both of these tools go beyond mere translation and must be used with caution. Discernment is essential to decide how to equivocate and assimilate, while preserving the transcultural elements of unity and ecumenicity with the church universal. As the Nairobi Statement says, “The fundamental values and meanings of both Christianity and of local cultures must be respected” (section 3.5).

THIRD: CHRISTIAN WORSHIP IS COUNTER-CULTURAL

Christians in the Middle East take their call to be peacemakers very seriously, intentionally designing worship that breaks down barriers and promotes reconciliation through prayers like the following:

Gracious God, you have promised through your prophets that Jerusalem will be home to many peoples, mother to many nations. Hear our prayers that Jerusalem, the city of your visitation, may be for all—Jews, Christians, and Muslims—a place to dwell with you and to encounter one another in peace. We make this prayer in Jesus’ name. Amen.5

In a meeting with a delegation of Christian leaders, the president of a Middle Eastern country said that Christians have a vital presence in the region because they offer a moderate, mediating voice in the vicious conflict. This prayer demonstrates how worship goes decidedly against the surrounding cultures of intolerance and war, refusing to bow down to the false gods of greed, racism, and uncompromising self-righteousness, choosing instead to transform people and cultural patterns by acting justly, loving mercy, and walking humbly with our God, the Prince of Peace (Isa 9:6; Mic 6:8).

Every culture contains some sinful, broken, dehumanizing elements that are contradictory to the gospel and present us with rival “secular liturgies that compete for our love.”6 Christian worship must resist the idolatries of a given culture. This doesn’t mean that we become anticultural; rather, it challenges us to become careful readers of our culture in light of biblical truths. Reflect on these words that both affirm and resist culture:

Wise is the church that seeks to be “in” but not “of” the world (John 15:19), resisting aspects of the culture that compromise the integrity of the gospel, and eagerly engaging its culture with the good news of the gospel of Jesus Christ, who comes to each culture, but is not bound by any culture.7

True worship challenges the oppression and injustice prevalent in local cultures (Rom 12:2). It makes room for grace to abound, freeing us to learn from another’s perspective, and it gives us courage to work together for reconciliation so that justice may “roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream!” (Amos 5:24).

In commenting on Psalm 73, John Witvliet writes, “Public worship, then as now, is a superb way to practice not being the center of the universe and learn to see the world right side up. Worship is, by the Spirit’s power, like spiritual cataract surgery that restores vision, clear and true.”8

FOURTH: CHRISTIAN WORSHIP IS CROSS-CULTURAL

FOURTH: CHRISTIAN WORSHIP IS CROSS-CULTURAL

At a seminar in North America on using songs from other cultures in worship, a participant asked this question: “I am a pastor of a small rural congregation, and my entire congregation is Anglo-European descendants, so why would we sing African or Asian or Latin songs in worship?”

This question betrays a faulty assumption that when we worship with songs, prayers, instruments, and visual arts from other cultures, we do it for “them”—meaning people who come from those cultures. While it is a great act of hospitality to make “them” feel welcome and included (a most commendable practice in the growing context of immigration and refugee resettlement), we must also realize that we do this for “us”—meaning people who feel at home in the commonly used language and musical style of “our” worship. Sharing worship resources cross-culturally expands our view of God and the church as transcending time and space, develops our repertoire of worship expressions, and crystalizes our understanding of the kingdom of heaven. Consider, for example, how this Brazilian rewriting of Psalm 137 confronts and enhances our view of community and justice:

By the rivers in Fortaleza, we sat down and cried

for the cholera victims;

In those who lived there

we saw sadness and we didn’t know what to say.

People who lived there

did not have songs on their lips.

They wanted joy

But, with neither water nor health

there was no way to be joyful.

How could we sing praise to the Lord

in the midst of such suffering?

If we forget you

If we don’t bring back water, health and joy.

Judge, Lord, our elites,

for their neglect and greed

have long mistreated us.

But remember Fortaleza,

your children in Ceara

that suffer from thirst and cholera;

Don’t let the earth go dry.9

There are, of course, many issues to consider when engaging in cross-cultural worship—such as authenticity, instrumentation, languages, ethnic identities, and respect. To do this fourth aspect properly, we must faithfully practice the first three aspects by asking questions like: What elements of transcultural faith are we celebrating? To what degree do these elements fit in our local context? What brokenness in my culture will these borrowed practices help redeem and reform? Asking such questions will help us avoid slipping into the danger of viewing our own cultural processes as superior to others.

One of the most common, though often unspoken, reasons for not engaging in global worship is our fear that somehow our own heritage will be lost. C. Michael Hawn responds to this fear most eloquently: “Liturgical plurality is not denying one’s cultural heritage of faith in song, prayer, and ritual. It is a conscious effort to lay one’s cultural heritage and perspective alongside another’s, critique each, and learn from the experience.”10

One of the most common, though often unspoken, reasons for not engaging in global worship is our fear that somehow our own heritage will be lost. C. Michael Hawn responds to this fear most eloquently: “Liturgical plurality is not denying one’s cultural heritage of faith in song, prayer, and ritual. It is a conscious effort to lay one’s cultural heritage and perspective alongside another’s, critique each, and learn from the experience.”10

The Nairobi Statement reminds us of what is at stake when we plan Christian worship. It helps us to major in question asking. The topic of worship practices is important not just for cultural anthropologists, missionaries, and missiologists, but for all Christian leaders and believers. And those of us who are novices in this area must enter the conversation with more questions than assertions.11

My hope and prayer is that local Christian communities may be instructed and inspired by the Nairobi Statement to see a third way when viewing the tension between worship and culture. Though sometimes difficult and unsettling, tension is not an evil that deserves rejection, but a four-way conversation that holds great potential to help us faithfully uphold the gospel’s beauty and power while engaging culture, and in so doing we follow the example of Christ.

comments