The Church’s Response to Pandemics Throughout History and the Lessons for Today

When Jesus called the Twelve and then the Seventy, He commissioned them to do the things He Himself was doing: They were to heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers, cast out demons and proclaim the coming of the kingdom. The early Church recognized that they were also called to do what Jesus did, though they did it differently than those commissioned during Jesus’ early life. Thus, Jesus set us free from our bondage to sin; we cannot do that, but we can set people free from slavery, and so early Christians purchased slaves specifically to free them. Similarly, Jesus was a healer, and so we too should tend the sick whether we have miraculous power to heal or not. Both activities, while good deeds in themselves, also served to advance the kingdom. In this article we will focus on tending the sick, especially during plagues and pandemics.

The first major epidemic faced by the early Church was the Antonine Plague (AD 166–189), brought to Rome by troops returning from campaigning against the Persians. The disease, most likely smallpox, killed 7–10% of the population of the Empire as a whole, with mortality in cities probably 13–15%. According to Dio Cassio, it killed 2,000 people per day in Rome during a particularly bleak period in AD 189. People understood that the disease was contagious, so in fear of their lives they would throw the sick out of their homes to die in the streets.

Galen, the most prominent physician of the age, fled Rome when the plague arrived to stay at his country estate.

He knew he could do nothing to heal its victims or to protect himself from contracting the disease. Christians on the other hand, ran into the plague. They recognized that all persons were made in the image of God, that Jesus died to redeem us body and soul, and thus that the sick deserved care. As a result, Christians began tending the sick at risk (and often at the cost) of their lives.

Galen, who viewed Christians as naïve and irrational, admitted that in some respects they were the equals of philosophers in that they had a contempt of death and its sequel that was evident every day. It is not clear whether he was referring to their willingness—even eagerness—to face martyrdom or to their actions in treating the sick. It may have been both: at about this same time a Roman Senator named Apollonius was put on trial for being a Christian and associated his upcoming death as a martyr with dying of disease, reportedly commenting, “It is often possible for dysentery and fever to kill; so I will consider that I am being destroyed by one of these.”

Since even basic nursing care can make a significant difference in survival rates in epidemics, Christian actions during the plague saved lives. Their undoubted courage and self-sacrifice in coming to the aid of their neighbors contributed to the rapid growth of Christianity. For example, when Irenaeus arrived in Lyons from Asia Minor, there were few Christians in the city. When the plague broke out, Christians tended and prayed for the sick, and by the time the plague ended, there were 200,000 believers in Lyons.

The following century brought the Plague of Cyprian, named after Cyprian, the bishop of Carthage who described the epidemic. It was a grim disease. In Cyprian’s words, “The intestines are shaken with a continual vomiting; the eyes are on fire with the infected blood; in some cases the feet or some parts of the limbs are taken off by the contagion of diseased putrefaction.” Experts think it may have been a fresh outbreak of smallpox or perhaps a hemorrhagic fever like Ebola. At its peak, the plague killed 5,000 people per day in the city of Rome alone. Up to two-thirds of the population of Alexandria, the second largest city of the Empire, died of the disease.

Cyprian’s fellow bishop, Dionysius of Alexandria, described the reaction of the pagans: “At the first onset of the disease, they pushed the sufferers away and fled from their dearest, throwing them into the roads before they were dead and treating unburied corpses as dirt, hoping thereby to avert the spread and but do what they might, they found it difficult to escape.” But not everyone abandoned the sick. Dionysius explains:

Most of our brother Christians showed unbounded love and loyalty, never sparing themselves and thinking only of one another. Heedless of danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ, and with them departed this life serenely happy; for they were infected by others with the disease, drawing on themselves the sickness of their neighbors and cheerfully accepting their pains. Many, in nursing and curing others, transferred their death to themselves and died in their stead.

As had happened with the Antonine Plague, Dionysius compares the ministry to the ill to martyrdom, whose literal meaning is bearing witness to Christ. Cyprian agreed. He commented, “Although this mortality had contributed nothing else, it has especially accomplished this for Christians and servants of God, that we have begun gladly to seek martyrdom while we are learning not to fear death.” He continued, “By the terrors of mortality and of the times, lukewarm men are heartened, the listless nerved, the sluggish awakened; deserters are compelled to return; heathens brought to believe; the congregation of established believers is called to rest; fresh and numerous champions are banded in heartier strength for the conflict, and having come into warfare in the season of death, will fight without fear of death, when the battle comes.”

“Heathens [were] brought to believe.” Christians attended to sick pagans, and in the process connected with new social networks, and as sociologist of religion Rodney Stark has demonstrated, religions spread best through social networks. When combined with the recognition of Christian courage, compassion, and service the entrance of the gospel into pagan social networks led to the explosive growth of Christianity in the Empire.

It is worth noting that Christians approached illness using the medical theory and practices of the day. Contrary to some stereotypes, the early Church did not attribute illness to demons, though they did recognize demonization as a real phenomenon. The difference between Christians and the physicians of the day was the willingness of believers to risk death to treat the sick, convinced that if they died it would only mean a transition to a better life; the physicians, on the other hand, fled.

In the fourth century, Constantine declared religious liberty in the Empire, effectively legalizing Christianity. Later that century, Theodosius I made Christianity the official religion of the Empire, though many pagans continued to live in and around Roman territory. Missions work to the Germanic tribes in northern Europe and central Europe continued. Politically, the Latin-speaking Western half of the Roman Empire largely disintegrated in the fifth century. In the East, the Emperor Justinian I began to rebuild the Empire, but his efforts were cut short by an outbreak of bubonic plague in 541 that killed approximately 40% of the population of the Empire and spread across Europe. There would be recurring outbreaks in various places around Europe until about 750.

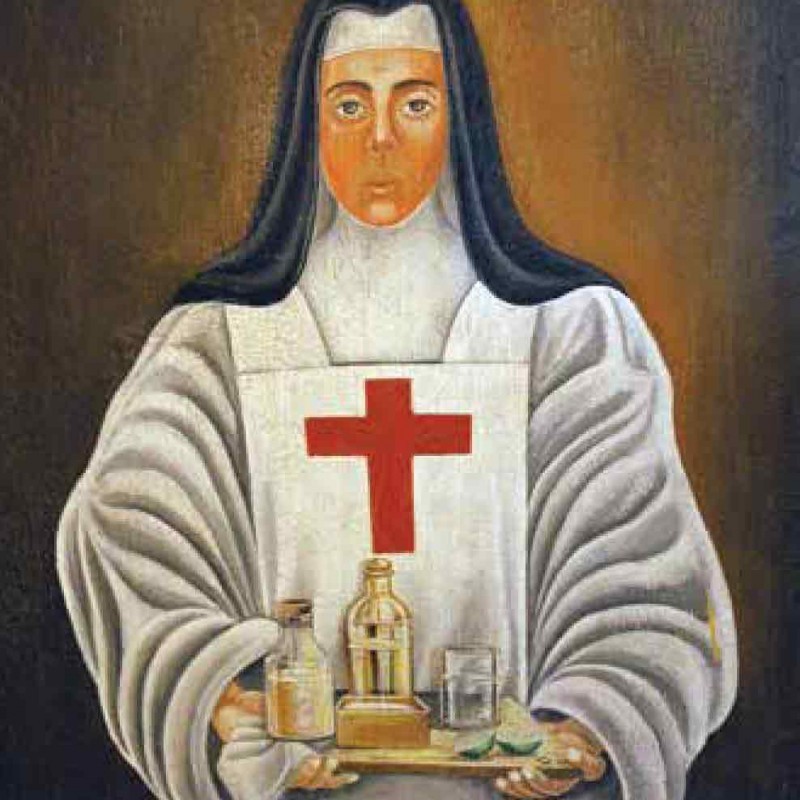

The world had changed in many ways with the spread of Christianity. By the late fourth century, Christians had founded hospitals in both the eastern and western halves of the Empire, and when the plague broke out, Christian hospitals, churches and monasteries provided much of the medical care for the sick. Once again, Christians also engaged in evangelistic work even as they treated the sick. John of Ephesus went to hard-hit areas, praying for the sick and seeing them healed and preaching a message of repentance, with thousands coming to faith. As far away as Ireland, the great missionary monks of the seventh century, known as the Twelve Apostles of Ireland, also ministered during the plague. In the end, the disease took at least three of them—Mobhi, Columba of Terryglass, and Ciaran of Clonmacnoise—along with their teacher Finnian of Clonard. Plague disappeared from Europe for 600 years. It came back in 1347 in Sicily and 1348 on the continent, and by 1351 it had killed just under half the people in Europe according to the most recent studies. Among the clergy, the percentage was even higher: they knew their duty was to minister to the sick and comfort the dying, and so they knowingly exposed themselves to the disease as they carried out their work. To most people, plague looked like the wrath of God, and so lay movements arose where men marched in processions from town to town beating themselves bloody to show God their sorrow for their sins. For its part, the Catholic Church soon disavowed these movements and called for their end. The reason was simple: if plague was God’s punishment for our sin, what did it say that both the nobles and the clergy were dying just like the others? The flagellants, as these groups were called, were just a small step from rejection of both church and government and so from complete anarchy.

But if plague wasn’t the wrath of God, what was it? The Pope turned to the theologians at the University of Paris for an answer. This may seem odd, but in the four-teenth century what we call “science”—studying the natural world—was considered a branch of theology. Since God created and sustains the universe, coming to understand how it works is a way of revealing the mind

of God. For their part, the theologians followed the example of the early church and came up with a natural explanation of the outbreak of plague based on the best medical knowledge of the day. They concluded that the disease was caused by a miasma, that is, by poisoned air pulled from the ground by the effect of a conjunction of planets, and thus the best way to deal with it was to eliminate, avoid, or “sweeten” foul odors. This would lead to a tremendous expansion of public sanitation in medieval cities as well as personal practices of dubious value to ward off plague.

While we might shake our heads at this as superstitious nonsense, it was based on the best medical theory they had, going back to the writings of the Roman physician Galen. This followed the example of the early Christians, who also based their approach to disease on the medicine of their day. In the context of the 14th century, it is perhaps most remarkable that the theologians advocated a natural explanation for plague and made recommendations to deal with it based on that explanation. This was in marked contrast to the Islamic world, for example. Earlier in the middle ages, Muslim medicine was far advanced from that of Europe, largely because Muslims had access to Greek medical treatises translated into Arabic by Syrian Christians such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq. By this point, however, a kind of Islamic fundamentalism had settled into Muslim Spain that rejected much of the knowledge in the Greek treatises as un-Islamic. According to the Quran, in an epidemic, Allah alone determines who gets ill and who lives or dies. Any attempt to prevent or treat plague was thus seen as apostacy since it amounted to an attempt to thwart the will of Allah. For all its fancifulness, the medieval Catholic Church’s explanation of plague had the virtue of attempting to find a natural explanation for it and thus a means of dealing with the disease.

There were recurring outbreaks of plague in Europe for over 300 years. Perhaps the best advice for responding to plague during these centuries came from Martin Luther. When plague broke out near Wittenberg, he was asked if it was permissible to flee. His answer was long, but his comments on his own approach are worth noting. He said that he would follow all the recommendations of the doctors, including “fumigating” his house (to drive off the miasma) and social isolation so that he would not be responsible for his own death or any other’s. If it were his time to die, he said, God would know where to find him. But while following medical advice as much as possible, he would not neglect his duties as a Christian and a pastor. If his neighbor needed him, if someone needed his comfort when sick or dying, it was his duty to be there. And if it cost him his life, so be it. He would not court trouble, but neither would he hide from it if his neighbor needed him.

After plague died out in Europe, the relationship of the Church to medicine changed. Even during the middle ages, medicine had become its own field of study; by the eighteenth century, it was increasingly separated from the clergy. The poor would receive charitable care from monasteries in Catholic areas, and nursing was almost entirely in the hands of sisters and nuns, but for those who could afford it, professional physicians increasingly handled medical issues. Clergy would still attend the dying, of course, but they had few other responsibilities to the sick.

The clergy still addressed questions of medical ethics. For example, in the 1700s, physicians developed an experimental form of inoculation against smallpox in which material from smallpox scabs was rubbed into scratches on the arm with the hope of generating an immune response without causing a serious case of the disease. Some Puritan pastors in New England condemned the practice as putting the Lord to the test and as being tantamount to suicide; others, such as Jonathan Edwards, advocated it as the only option they had for mitigating an epidemic disease that had killed thousands and left uncounted others disfigured. Edwards allowed himself to be inoculated, which unfortunately led to his death by smallpox. [Editor’s Note: During the U.S. Revolutionary War, Abigail Adams, wife of future president John Adams, carried out the same type of inoculation upon herself and her children and they all survived.]

Moving into the 1800s, missionary activity often included a medical component. Hudson Taylor himself was a trained physician and worked as a medical missionary in his first trip to China. There were two reasons why medical missions was such an important component of missionary strategy. First, Christianity has always affirmed the importance of the body as evident in the history of Christian responses to epidemics. As a result, wherever Christianity has gone, hospitals have followed (In the same way, Christianity has always affirmed the importance of the mind, and so wherever Christianity has gone, schools have followed). Jesus healed people’s bodies, and we should do the same to the best of our abilities. Second, medical work is an important and effective door opener for the gospel. It brings us into contact with people at their point of need, builds relationships with them and gives us access to their social networks. And since the gospel flies best on the wings of relationships, the connections established through medical work are an important entry point for disciple-making. In contemporary DMM contexts, fixed and mobile medical clinics, barefoot doctors and dentists, and other healthcare ministries have opened the door to disciple-making and church-planting that have transformed countless communities around the world.

Along with formal medical treatment, throughout history we also see the importance of prayer for the sick, particularly in regions without access to modern medicine. It is not at all uncommon to find reports of miraculous healings in answer to prayer in epidemics in various parts of the world over the last 200 years and in Disciple Making Movements today.

So what lessons can we learn from all of this in our time of pandemic? I would suggest five.

First, Christians have a responsibility to deal with disease. Jesus did; He called the Apostles and the Seventy to it, and He continues to call us to it. Our bodies are not just an add-on; they are such an essential part of who we are that we will get them back transformed in the resurrection. Thus, taking care of people’s health is part of our responsibility before God.

Second, from the earliest centuries Christians have recognized medicine as a good gift of God and have utilized the best medical knowledge and technologies available; they have also advocated following medical advice. As we deal with Covid-19 and other diseases, we should be following their example.

Third, Christians have acted courageously and at great personal risk in helping the sick. While we should follow medical advice, we cannot allow that advice to overrule our responsibilities to our neighbor. Loving our neighbor may mean different things at different times. It may mean social distancing so we do not risk infecting them as Luther suggested, but it may also mean going into areas where we risk contracting the disease ourselves. If we do go into those areas, we should take all possible precautions against infection but recognize with Paul that “for me, to live is Christ and to die is gain.”

Fourth, we must not neglect prayer. Whether we can provide medical assistance or not, we can and should always pray for the sick. God continues to heal in response to prayer, and we would be foolish not to turn to Him in all our efforts to deal with illness and its impact on lives and communities.

Fifth, we pray and do our medical work with all, regardless of their openness to the gospel, but we look for those who are open to engage in spiritual conversations with the goal of making disciples. We should look on every service we do for others as an opportunity to build relationships, connect with social networks, and begin the process of disciple-making with all who are open. In this way we fulfill all of our callings in the world: we fulfill the cultural mandate of Genesis by working to fix what is broken in the world; we fulfill the great commandment by loving our neighbor; and we fulfill the Great Commission by making disciples.

comments